🤔How to Distinguish Conductors and Insulators by Ground State Only?

This note aims to elucidate the connection between the conductivity of a many-body system and the quantum geometry of its ground state, and to explain how to distinguish between conductors and insulators solely based on the “locality” of the ground state wavefunction.

Introduction

“Distinguishing conductors and insulators by only looking at the ground state”—this argument seems a bit outrageous.

The Band Theory of the 1930s (to some extent) explained the difference between conductors and insulators. At the non-interacting level, conductors and insulators can be distinguished by whether the ground state energy bands are filled. If the valence band is filled and there is a band gap $E_g > 0$ separating it from the conduction band, it is an insulator; otherwise, it is a conductor. Here, the band gap $E_g$ is used to distinguish them, but defining $E_g$ requires knowing the energy of excited states, thus inevitably involving excited state properties.

However, the Mott Insulator (caused by strong electron-electron correlation) proposed in 1949 and the Anderson Insulator (caused by strong disorder) proposed in 1958 pointed out the loopholes of Band Theory in distinguishing conductors and insulators. That is, the insulating mechanism of many-body systems involves not only filled valence bands but also strong correlations and disorder. Similarly, besides the absence of a band gap being a mechanism for conductivity, some disordered metal alloys can be conductors. Conversely, in disordered alloy systems, even without a band gap, they might still be insulators, which is exactly the Anderson Localization where localized states cannot stably transport current.

Moreover, a many-body system might not have a lattice at all. We urgently need a more universal indicator to judge the conductive properties of many-body systems.

Phenomenologically, the difference between a conductor and an insulator lies in the difference in DC conductivity $\operatorname{Re}\sigma(\omega\rightarrow 0)$, because general insulators can also conduct electricity under AC current. Or they can be distinguished by electric polarization: in insulators, electrons are bound and can only move near atoms, resulting in obvious electric polarization phenomena; while in conductors, electrons tend to move freely, and an external electric field will cause them to flow freely, so there is no well-defined electric polarization.

We can always calculate conductivity or polarizability through Linear Response Theory to distinguish conductors and insulators, but this still requires considering the properties of excited states.

However, Kohn proposed in his 1964 paper “Theory of the insulating state” that the conductivity of a many-body system can be judged by the “locality” of the ground state many-body wavefunction in the many-body configuration space.

https://journals.aps.org/pr/abstract/10.1103/PhysRev.133.A171

In the late 20th century, Resta and others noticed that this degree of locality could be better characterized by the second cumulant moment $\langle r_\alpha r_\beta \rangle_c$ (“c” for “cumulant”) of the many-body ground state wavefunction, and revealed its essence of Quantum Geometry.

https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.370

So first, let’s clarify how to define the degree of locality of a wavefunction.

Wannierizability & Quantum Geometry

It needs to be clarified here that the so-called “locality of the ground state many-body wavefunction in many-body configuration” is different from the locality of a single-particle wavefunction, but there are similarities in definition. Moreover, deriving it from the perspective of single-particle wavefunctions is simpler, so we will first introduce the definition of locality for single-particle wavefunctions, discuss its properties, and then generalize it to the many-body case in the papers of Kohn, Resta, et al.

Taking a solid-state band system as an example, whether it is an insulator or a conductor, its single-electron eigenstates are extended Bloch wavefunctions. However, we can transform these spatially extended Bloch eigenstates into spatially localized Wannier Functions via Fourier Transform.

The transformation relationship between the Wannier function $|\mathbf{R} n\rangle$ and the Bloch wavefunction $\left|\psi_{n \mathbf{k}}\right\rangle$:

$$ \begin{aligned} \left|\psi_{n \mathbf{k}}\right\rangle=\sum_{\mathbf{R}} e^{i \mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{R}}|\mathbf{R} n\rangle \Leftrightarrow |\mathbf{R} n\rangle=\frac{1}{N} \sum_{\mathbf{k}} e^{-i \mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{R}}\left|\psi_{n \mathbf{k}}\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$The degree of locality of the Wannier wavefunction is related to the gauge selection of the energy band. If we add a phase (gauge) related to $\mathbf{k}$ to the Bloch wavefunction, it remains an eigenstate.

$$ \begin{aligned} \left|\tilde{\psi}_{n \mathbf{k}}\right\rangle=e^{i \varphi_n(\mathbf{k})}\left|\psi_{n \mathbf{k}}\right\rangle \ \Rightarrow\ \hat{H}\left|\tilde{\psi}_{n \mathbf{k}}\right\rangle = \epsilon_n(\mathbf{k}) \left|\tilde{\psi}_{n \mathbf{k}}\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$For content on how to adjust the gauge to achieve maximum localization of the Wannier function, one can refer to Vanderbilt’s 1997 PRB paper, “Maximally localized generalized Wannier functions for composite energy bands” and the 2012 RMP, “Maximally localized Wannier functions: Theory and applications”:

https://journals.aps.org/prb/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevB.56.12847

https://journals.aps.org/rmp/abstract/10.1103/RevModPhys.84.1419

Vanderbilt defined the degree of locality of the Wannier function using the standard deviation of its spatial distribution, the so-called Spread Functional, also known as Quadratic Spread:

$$ \begin{aligned} \Omega=\left[\left\langle\mathbf{0} n\left|r^2\right| \mathbf{0} n\right\rangle-\langle\mathbf{0} n|\mathbf{r}| \mathbf{0} n\rangle^2\right]=\left[\left\langle r^2\right\rangle_n-\overline{\mathbf{r}}_n^2\right] \end{aligned} $$This Spread Functional relates to the gauge selection but can be divided into a gauge-invariant part $\Omega_{\mathrm{I}}$ and a gauge-dependent part $\tilde{\Omega}$:

$$ \begin{aligned} \Omega=\Omega_{\mathrm{I}}+\tilde{\Omega} \end{aligned} $$Among them, the gauge-invariant part $\Omega_{\mathrm{I}}$ is also called the second cumulant moment of the Wannier function:

$$ \begin{aligned} \Omega_{\mathrm{I}}=\sum_{\alpha}\left\langle 0 n\left|r_\alpha Q r_\alpha\right| 0 n\right\rangle=\sum_\alpha \operatorname{Tr}\left[P r_\alpha Q r_\alpha\right] \end{aligned} $$$P$ is the projection operator onto the band under consideration:

$$ \begin{aligned} P =\frac{1}{N} \sum_{\mathbf{k}}\left|\psi_{n \mathbf{k}}\right\rangle\langle\psi_{n \mathbf{k}}|=\sum_{\mathbf{R}}| \mathbf{R} n\rangle\langle\mathbf{R} n| \end{aligned} $$This part is related to the Quantum Geometry of the single-particle band:

$$ \begin{aligned} \Omega_{\mathrm{I}} & = \sum_\alpha \sum_k \langle \partial_{k_{\alpha}} u_{k}^n | \left( \mathbb{I} - |u_k^n \rangle \langle u_k^n | \right) | \partial_{k_{\alpha}} u_{k}^n \rangle \end{aligned} $$The gauge-dependent part $\tilde{\Omega}$ is a non-negative value:

$$ \begin{aligned} \tilde{\Omega}=\sum_{\mathbf{R} m \neq 0 n}|\langle\mathbf{R} m|\mathbf{r}| \mathbf{0} n\rangle|^2 \end{aligned} $$So we always have:

$$ \begin{aligned} \Omega \geq \Omega_{\mathrm{I}} \end{aligned} $$Detailed derivation of this part can be found in my note:

https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/629079639

It can be seen that the gauge-invariant part of the Quadratic Spread of the Wannier function defines the lower limit of its locality and establishes a direct connection with the Quantum Geometry of the single-particle band.

In other words, Quantum Geometry can, to a certain extent, reflect the degree of locality of the system (currently a single-particle system).

Inspired by this, we can define the Quantum Geometry of a many-body system, examine the “locality” information of the many-body wavefunction it contains, and discuss how this ground state property—the “locality” of the many-body ground state wavefunction—determines the conductivity of the many-body system.

Many-Body Quantum Geometry

Similarly, let’s define the Quantum Geometry of a many-body system. First, write down the most general many-body Hamiltonian:

$$ \begin{aligned} \hat{H}=\frac{1}{2 m_e} \sum_{i=1}^N\left|\mathbf{p}_i+\frac{e}{c} \mathbf{A}\left(\mathbf{r}_i\right)\right|^2+\hat{V}(\\{\mathbf{r}_i\\}) \end{aligned} $$However, at this time, the system does not necessarily have translational symmetry, so the Quantum Geometry construction method of the original single-particle band theory cannot be directly applied here, and the momentum of a single electron cannot be directly used as the parameter space.

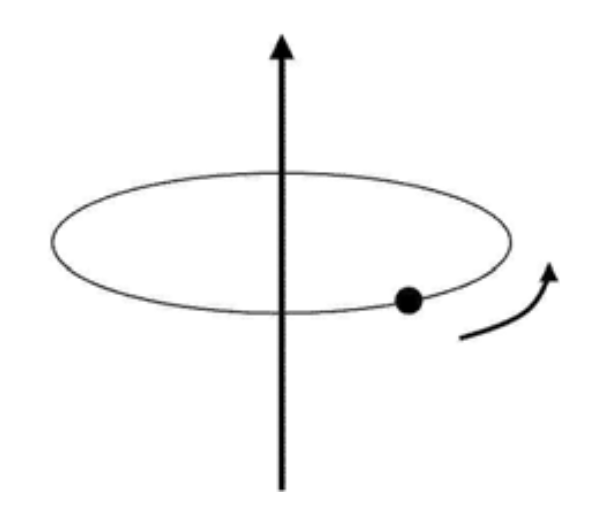

To find a parameter space where Quantum Geometry can be constructed, we perform a gauge transformation on the many-body Hamiltonian:

$$ \begin{aligned} \hat{H}(\boldsymbol{\kappa}) \equiv e^{-i \boldsymbol{\kappa} \cdot \hat{\mathbf{r}}} \hat{H} e^{i \boldsymbol{\kappa} \cdot \hat{\mathbf{r}}} \end{aligned} $$Where $\hat{\mathbf{r}} \equiv \sum_i \hat{\mathbf{r}}_i$.

That is,

$$ \begin{aligned} \hat{H}(\boldsymbol{\kappa})=\frac{1}{2 m_e} \sum_{i=1}^N\left|\mathbf{p}_i+\frac{e}{c} \mathbf{A}\left(\mathbf{r}_i\right)+\hbar \boldsymbol{\kappa}\right|^2+\hat{V}(\\{(\mathbf{r}_i\\}) \end{aligned} $$At this time, different parameters $\boldsymbol{\kappa}$ correspond to different many-body energy spectra and eigen-wavefunctions:

$$ \begin{aligned} H(\boldsymbol{\kappa})|\Psi(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\rangle=E(\boldsymbol{\kappa})|\Psi(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\rangle \end{aligned} $$This is equivalent to adding a constant magnetic vector potential, which can be understood using the magnetic flux in a 1D ring, where $\kappa \propto$ flux $\Phi$ inside the ring.

The most important thing for a many-body system is the ground state. We examine the mapping from the parameter space $\boldsymbol{\kappa}$ to the ground state wavefunction $|\Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\rangle$ and use this to construct the Quantum Geometric Tensor of the ground state wavefunction space:

$$ \begin{aligned} \eta_{\alpha \beta}(\boldsymbol{\kappa})=\left\langle\partial_\alpha \Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})|\hat{Q}(\boldsymbol{\kappa})| \partial_\beta \Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$Where $\hat{Q}(\boldsymbol{\kappa})=\hat{1}-\hat{P}(\boldsymbol{\kappa})$, and $\hat{P}(\boldsymbol{\kappa})$ is the projection operator of the ground state wavefunction space:

$$ \begin{aligned} \hat{P}(\boldsymbol{\kappa})=\left|\Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle\left\langle\Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right| \end{aligned} $$Similar to band geometry, the real part is a Symmetric Tensor, called the Fubini-Study metric:

$$ \begin{aligned} g_{\alpha \beta}(\boldsymbol{\kappa}) & =\operatorname{Re}\left\langle\partial_\alpha \Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa}) \mid \partial_\beta \Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle \\ & -\left\langle\partial_\alpha \Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa}) \mid \Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle\left\langle\Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa}) \mid \partial_\beta \Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle \\ & =\operatorname{Re}\left\langle\partial_\alpha \Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})|\hat{Q}(\boldsymbol{\kappa})| \partial_\beta \Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$The imaginary part is an Anti-symmetric Tensor, which is the Berry Curvature:

$$ \begin{aligned} \Omega_{\alpha \beta}(\boldsymbol{\kappa})=-2 \operatorname{Im}\left\langle\partial_\alpha \Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})|\hat{Q}(\boldsymbol{\kappa})| \partial_\beta \Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$Similar to the single-particle case, it can also be written in the form of a “sum of states” using first-order perturbation theory:

$$ \begin{aligned} \left|\Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa}+\Delta \boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle-\left|\Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle \simeq \sum_{n \neq 0}^{\prime}\left|\Psi_n(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \times \frac{\left\langle\Psi_n(\boldsymbol{\kappa})|[H(\boldsymbol{\kappa}+\Delta \boldsymbol{\kappa})-H(\boldsymbol{\kappa})]| \Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle}{E_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})-E_n(\boldsymbol{\kappa})} \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \left|\partial_\alpha \Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle=\sum_{n \neq 0}^{\prime}\left|\Psi_n(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle \frac{\left\langle\Psi_n(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\left|\partial_\alpha H(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right| \Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle}{E_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})-E_n(\boldsymbol{\kappa})} . \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \eta_{\alpha \beta}(\kappa)= \sum_{n \neq 0}^{\prime} \frac{\left\langle\Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\left|\partial_\alpha H(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right| \Psi_n(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle\left\langle\Psi_n(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\left|\partial_\beta H(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right| \Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle}{\left[E_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})-E_n(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right]^2} \end{aligned} $$It should be noted that this sum of states formula fails when there is no gap or ground state degeneracy (where first-order perturbation theory fails), but this does not mean the definition of Quantum Geometry fails. Many-body systems also exhibit fascinating Ground State Degeneracy, where the ground state wavefunction and its Quantum Geometry can be extended to higher-dimensional non-Abelian forms (generalization of non-Abelian Berry Connection).

Due to space limitations, we only discuss the case of non-degenerate Ground State. Interested readers can generalize and calculate the non-Abelian Quantum Geometry of systems such as Fractional Quantum Hall systems.

Quantum Geometry & Localization

Let’s extend the second cumulant moment of the position operator describing the degree of single-particle localization, i.e., the gauge-invariant part of the Spread Functional $\Omega_I$, to the many-body case to describe the “locality” of the many-body wavefunction.

We notice:

$$ \begin{aligned} \hat{H}(\boldsymbol{\kappa}) \equiv e^{-i \boldsymbol{\kappa} \cdot \hat{\mathbf{r}}} \hat{H} e^{i \boldsymbol{\kappa} \cdot \hat{\mathbf{r}}} \end{aligned} $$Assuming $\left|\Psi_0\right\rangle$ is the non-degenerate ground state of $\hat{H}$, we can easily write the ground state of $\hat{H}(\boldsymbol{\kappa})$ (assuming open boundary conditions for now; periodic boundary conditions are more complex):

$$ \begin{aligned} \left|\Psi_0(\boldsymbol{\kappa})\right\rangle=e^{-i \boldsymbol{\kappa} \cdot(\hat{\mathbf{r}}-\mathbf{d})}\left|\Psi_0\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$Where $\mathbf{d}=\left\langle\Psi_0|\hat{\mathbf{r}}| \Psi_0\right\rangle$. This term only contributes a constant phase, so it has no effect.

To find the Quantum Geometry, we differentiate:

$$ \begin{aligned} \left|\nabla_{\boldsymbol{\kappa}} \Psi_0\right\rangle=-i(\hat{\mathbf{r}}-\mathbf{d})\left|\Psi_0\right\rangle=-i \hat{Q}(0) \hat{\mathbf{r}}\left|\Psi_0\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$Thus obtaining:

$$ \begin{aligned} \eta_{\alpha \beta}(0) &=\left\langle\Psi_0\left|\hat{r}_\alpha \hat{Q}(0) \hat{r}_\beta\right| \Psi_0\right\rangle \\ &=\left\langle\Psi_0\left|\hat{r}_\alpha \hat{r}_\beta\right| \Psi_0\right\rangle-\left\langle\Psi_0\left|\hat{r}_\alpha\right| \Psi_0\right\rangle\left\langle\Psi_0\left|\hat{r}_\beta\right| \Psi_0\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$Where $\hat{\mathbf{r}} \equiv \sum_i \hat{\mathbf{r}}_i$. It is hard not to notice that this is equivalent to the variance of the ground state wavefunction coordinate distribution, i.e., the second cumulant moment. It reflects the “locality” of the ground state wavefunction electron distribution in real space.

However, this quantity is an extensive quantity (like volume), and will scale with $N$ in the thermodynamic limit $N\rightarrow\infty$. In order to compare this “locality” between different systems, we average it for each electron to make it a comparable intensive quantity (like pressure). Of course, this can also be achieved by changing the normalization definition of the wavefunction:

$$ \begin{aligned} \left\langle r_\alpha r_\beta\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}} =\eta_{\alpha \beta}(0) / N \end{aligned} $$It is not difficult to find that, unlike the degree of localization of the single-particle Wannier wavefunction which requires integration over all momenta $k$, $\Omega_I \propto \int_{BZ}d^dk \operatorname{tr}g(k)$, here we only need the information of the parameter space $\boldsymbol{\kappa} = 0$, that is, the ground state information of the original system.

$$ \begin{aligned} \left\langle r_\alpha r_\beta\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}}= \frac{1}{N} \left(\left\langle\Psi_0\left|\hat{r}_\alpha \hat{r}_\beta\right| \Psi_0\right\rangle-\left\langle\Psi_0\left|\hat{r}_\alpha\right| \Psi_0\right\rangle\left\langle\Psi_0\left|\hat{r}_\beta\right| \Psi_0\right\rangle \right) \end{aligned} $$For convenience of derivation later (to better compare with the conductivity formula), it can also be written in the form of “sum of states”:

$$ \begin{aligned} \left\langle r_\alpha r_\beta\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}}= \frac{1}{N} \sum_{n \neq 0}^{\prime} \frac{\left\langle\Psi_0\left|\partial_\alpha \hat{H}(0)\right| \Psi_n\right\rangle\left\langle\Psi_n\left|\partial_\beta \hat{H}(0)\right| \Psi_0\right\rangle}{\left(E_0-E_n\right)^2} \end{aligned} $$Where,

$$ \begin{aligned} \nabla_\kappa \hat{H}(0) =\frac{\hbar}{m_e} \sum_{i=1}^N\left[\mathbf{p}_i+\frac{e}{c} \mathbf{A}\left(\mathbf{r}_i\right)\right] = \hbar \hat{\mathbf{v}} \end{aligned} $$This is effectively the momentum (velocity) operator, so it can be further rewritten as:

$$ \begin{aligned} \left\langle r_\alpha r_\beta\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}} =\frac{1}{N} \sum_{n \neq 0}^{\prime} \frac{\left\langle\Psi_0\left|\hat{v}_\alpha\right| \Psi_n\right\rangle\left\langle\Psi_n\left|\hat{v}_\beta\right| \Psi_0\right\rangle}{\left(E_0-E_n\right)^2/\hbar^2} \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} =\frac{1}{N} \sum_{n \neq 0}^{\prime} \frac{\left\langle\Psi_0\left|\hat{v}_\alpha\right| \Psi_n\right\rangle\left\langle\Psi_n\left|\hat{v}_\beta\right| \Psi_0\right\rangle}{\omega_{0 n}^2} \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \omega_{0 n}= \left(E_n-E_0\right) / \hbar \end{aligned} $$But we must bear in mind, this second cumulant moment is purely a locality property of the ground state wavefunction, independent of excited states.

To summarize, we generalized the single-particle Quantum Geometry to the many-body ground state wavefunction space, and found that the Quantum Geometry of the many-body ground state wavefunction space (divided by the total number of electrons N) can characterize the locality of the many-body ground state wavefunction distribution in real space, and this is a ground state property, independent of excited states.

Our ultimate goal is to use this purely ground state property to distinguish between conductors and insulators, which seemingly require excited state properties to distinguish.

Localization & Conductivity

Linear Response Theory

We can quickly get the conductivity of a many-body system using Linear Response Theory. Interested students can check my Linear Response Theory note:

https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/477550302

$$ \begin{aligned} \sigma_{\alpha \beta}(\omega)=\frac{i e^2}{\hbar L^3} \lim_{\eta \rightarrow 0+} \sum_{n \neq 0}^{\prime} \frac{1}{\omega_{0 n}}& \left(\frac{\left\langle\Psi_0\left|\hat{v}_\alpha\right| \Psi_n\right\rangle\left\langle\Psi_n\left|\hat{v}_\beta\right| \Psi_0\right\rangle}{\omega-\omega_{0 n}+i \eta}\right. \\ & \left.+\frac{\left\langle\Psi_0\left|\hat{v}_\beta\right| \Psi_n\right\rangle\left\langle\Psi_n\left|\hat{v}_\alpha\right| \Psi_0\right\rangle}{\omega+\omega_{0 n}+i \eta}\right) \end{aligned} $$The real part of this conductivity is the dissipative term, and the imaginary part is the fluctuation term. We usually examine the dissipative nature of conductance, so we focus on its real part $\sigma_{\alpha \beta}(\omega)$.

The real part of conductivity $\sigma_{\alpha \beta}(\omega)$ can be divided into symmetric and anti-symmetric parts (note $\omega > 0$ and $\omega_{0n} > 0$):

$$ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \beta}^{(+)}(\omega)=\frac{\pi e^2}{\hbar L^3} \sum_{n \neq 0}^{\prime} \frac{\mathcal{R}_{n, \alpha \beta}}{\omega_{0 n}} \delta\left(\omega-\omega_{0 n}\right) \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \beta}^{(-)}(\omega)=\frac{2 e^2}{\hbar L^3} \sum_{n \neq 0}^{\prime} \frac{\mathcal{I}_{n, \alpha \beta}}{\omega_{0 n}^2-\omega^2} \end{aligned} $$Where,

$$ \begin{aligned} \mathcal{R}_{n, \alpha \beta}=\operatorname{Re}\left\langle\Psi_0\left|\hat{v}_\alpha\right| \Psi_n\right\rangle\left\langle\Psi_n\left|\hat{v}_\beta\right| \Psi_0\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \mathcal{I}_{n, \alpha \beta}=\operatorname{Im}\left\langle\Psi_0\left|\hat{v}_\alpha\right| \Psi_n\right\rangle\left\langle\Psi_n\left|\hat{v}_\beta\right| \Psi_0\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$In the derivation we used,

$$ \begin{aligned} \lim_{\eta \rightarrow 0+} \frac{1}{x + i\eta} = \mathcal{P}\frac{1}{x} - i \pi \delta(x) \end{aligned} $$Comparing with the sum of states form of the second cumulant moment $\left\langle r_\alpha r_\beta\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}}$ describing the locality of the many-body ground state wavefunction obtained earlier:

$$ \begin{aligned} \left\langle r_\alpha r_\beta\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}} =\frac{1}{N} \sum_{n \neq 0}^{\prime} \frac{\left\langle\Psi_0\left|\hat{v}_\alpha\right| \Psi_n\right\rangle\left\langle\Psi_n\left|\hat{v}_\beta\right| \Psi_0\right\rangle}{\omega_{0 n}^2} \end{aligned} $$It is not difficult to find,

$$ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{Re}\left\langle r_\alpha r_\beta\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}}=\frac{1}{N} \sum_{n \neq 0}^{\prime} \frac{\mathcal{R}_{n, \alpha \beta}}{\omega_{0 n}^2} \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{Im}\left\langle r_\alpha r_\beta\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}}=\frac{1}{N} \sum_{n \neq 0}^{\prime} \frac{\mathcal{I}_{n, \alpha \beta}}{\omega_{0 n}^2} \end{aligned} $$Furthermore, the SWM Formula (I.Souza, T.Wilkens, R.M.Martin, 2000) can be proven:

$$ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{Re}\left\langle r_\alpha r_\beta\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}} =\frac{\hbar L^3}{\pi e^2 N} \int_0^{\infty} \frac{d \omega}{\omega} \operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \beta}^{(+)}(\omega) \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{Im}\left\langle r_\alpha r_\beta\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}} =\frac{\hbar L^3}{2 e^2 N} \operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \beta}^{(-)}(0) \end{aligned} $$SWM Formula

When defining conductors and insulators phenomenologically, we focus on their static longitudinal conductivity, i.e., $\lim_{\omega \rightarrow 0}\sigma_{\alpha \alpha}(\omega)$.

We focus on the static field $\omega \rightarrow 0$ because insulators can also conduct electricity under AC current; and we focus on longitudinal conductivity because even if transverse conductivity (e.g., Hall conductivity) is non-zero, we still call it an insulator if longitudinal conductivity is zero (e.g., Quantum Hall Insulator, Chern Insulator).

We can find that the information at $\omega \rightarrow 0$ is not easily directly linked to $\left\langle r_\alpha r_\beta\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}}$, but through the SWM formula above, we can indirectly examine the information at $\omega \rightarrow 0$.

Focusing on the real part of the longitudinal information of the SWM formula (since the index $\alpha$ is the same, $\operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \alpha} = \operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \alpha}^{(+)}$):

$$ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{Re}\left\langle r_\alpha r_\alpha\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}} =\frac{\hbar L^3}{\pi e^2 N} \int_0^{\infty} \frac{d \omega}{\omega} \operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \alpha}(\omega) \end{aligned} $$The f-sum rule can be used to prove the convergence of the integral at $\omega \rightarrow \infty$:

$$ \begin{aligned} \int_0^{\infty} d \omega \operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \alpha}(\omega) = \frac{\pi e^2 N}{2 m_e L^3} \end{aligned} $$Then, the convergence of the integral (whether $\operatorname{Re}\left\langle r_\alpha r_\alpha\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}} $ is finite or not) depends on the information of conductivity at $\omega \rightarrow 0$.

And whether $\operatorname{Re}\left\langle r_\alpha r_\alpha\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}}$ is finite is directly related to the locality of the many-body system. We can define: if $\operatorname{Re}\left\langle r_\alpha r_\alpha\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}}$ is finite, the many-body ground state is “Localized”; if it diverges, it is “Delocalized”.

Through the above derivation, we have successfully expressed the “locality” of the many-body ground state wavefunction quantitatively and linked it to the system’s static longitudinal conductivity.

Note, this is only related to ground state information!

Metal or Insulator?

Finally, we can answer the question at the beginning of this article: How to distinguish conductors and insulators by only looking at the ground state?

For systems with a band gap, since all excitation energies $\hbar \omega_{0n} \geq E_g$, from the linear response formula of conductivity $\operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \beta}^{(+)}(\omega) \simeq \sum \delta\left(\omega-\omega_{0 n}\right)$, it is obvious that the conductivity is 0 when $\omega \rightarrow 0$, so it is an insulator.

Thus, the lower limit of the integral for $\operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \beta}^{(+)}(\omega) \simeq \sum \delta\left(\omega-\omega_{0 n}\right)$ can be changed to $E_g/\hbar > 0$:

$$ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{Re}\left\langle r_\alpha r_\alpha\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}} =\frac{\hbar L^3}{\pi e^2 N} \int_{E_{\mathrm{g} /} \hbar}^{\infty} \frac{d \omega}{\omega} \operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \alpha}(\omega) \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} <\frac{\hbar L^3}{\pi e^2 N} \int_0^{\infty} \frac{d \omega}{E_{\mathrm{g}}/\hbar} \operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \alpha}(\omega) =\frac{\hbar^2}{2 m_e E_{\mathrm{g}}} \end{aligned} $$This shows that $\operatorname{Re}\left\langle r_\alpha r_\alpha\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}}$ has an upper bound and is finite, which corresponds to the localized many-body ground state we defined earlier.

In this way, we can determine whether the system is an insulator or a conductor entirely by the locality of the many-body ground state:

$$ \begin{aligned} \text{Many-body ground state "Localized"} \Leftrightarrow \text{System is Insulator}(E_g>0) \end{aligned} $$Conversely, for a conductor (metal) with static longitudinal conductivity $\lim_{\omega \rightarrow 0} \operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \alpha}(\omega) > 0$, we find that the above integral at $\omega \rightarrow 0$:

$$ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{Re}\left\langle r_\alpha r_\alpha\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}} \simeq \frac{\hbar L^3 }{\pi e^2 N} \lim_{\omega \rightarrow 0} \operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \alpha}(\omega)\int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{d \omega}{\omega} \end{aligned} $$Obviously diverges at $\omega \rightarrow 0$, so $\operatorname{Re}\left\langle r_\alpha r_\alpha\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}} = \infty$.

Thus we have:

$$ \begin{aligned} \text{Many-body ground state "Delocalized"} \Leftrightarrow \text{System is Conductor} \end{aligned} $$Of course, there is a special case, the gapless case $E_g = 0$. At this time, whether the many-body ground state is “localized” or not still depends on the behavior of the static longitudinal conductivity $\lim_{\omega \rightarrow 0} \operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \alpha}(\omega)$. For example, if $\lim_{\omega \rightarrow 0} \operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \alpha}(\omega) \propto \omega^{\alpha \geq 1}$, then the many-body ground state is still localized and is an insulator; conversely, if $\lim_{\omega \rightarrow 0} \operatorname{Re} \sigma_{\alpha \alpha}(\omega) \propto \omega^{\alpha < 1}$, then the many-body ground state is delocalized and is a conductor.

Among them, the strongly disordered Anderson Insulator belongs to the former, because although outside the mobility edge of the disordered system is the energy spectrum (which can make the system gapless), the electronic states outside the mobility edge undergo Anderson Localization and do not contribute to conductivity, so it is still an insulator overall; while band metals or weakly disordered, weakly correlated conductor systems belong to the latter.

In this way, for any many-body system (regardless of symmetry, disorder, strong correlation, etc.), we can distinguish all insulators and conductors just by looking at the electron locality of the many-body ground state wavefunction.

Summary

$$ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{Re}\left\langle r_\alpha r_\alpha\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}} < \infty \Leftrightarrow \text{Many-body ground state "Localized"} \Leftrightarrow \text{System is Insulator} \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{Re}\left\langle r_\alpha r_\alpha\right\rangle_{\mathrm{c}} = \infty \Leftrightarrow \text{Many-body ground state "Delocalized"} \Leftrightarrow \text{System is Conductor} \end{aligned} $$Reference

[1] Kohn W. Theory of the insulating state. Physical review, 1964, 133(1A): A171.

[2] Resta, R., & Sorella, S. (1999). Electron localization in the insulating state. Physical Review Letters, 82(2), 370.

[3] Souza, I., Wilkens, T., & Martin, R. M. (2000). Polarization and localization in insulators: Generating function approach. Physical Review B, 62(3), 1666.

[4] Marzari, N., Mostofi, A. A., Yates, J. R., Souza, I., & Vanderbilt, D. (2012). Maximally localized Wannier functions: Theory and applications. Reviews of Modern Physics, 84(4), 1419.

[5] Lee, C. H., Thomale, R., & Qi, X. L. (2013). Pseudopotential formalism for fractional Chern insulators. Physical Review B, 88(3), 035101.

[6] Marzari, N., & Vanderbilt, D. (1997). Maximally localized generalized Wannier functions for composite energy bands. Physical review B, 56(20), 12847.

[7] Resta, R. (2002). Why are insulators insulating and metals conducting?. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter, 14(20), R625.

[8] Resta, R. (2022). Geometry and topology in electronic structure theory. Università degli Studi di Trieste.