🧐Fractional Quantum Hall Effect (FQHE), Fractional Anomalous Quantum Hall Effect (FAQHE) and Fractional Chern Insulator (FCI)

This note is approximately 10,000 words long and aims to help readers get started with Fractional Quantum Hall Effect (FQHE), Fractional Anomalous Quantum Hall Effect (FAQHE), and Fractional Chern Insulators (FCI). This article represents only my personal perspective and may contain errors; I welcome corrections from readers. Below is the main text.

Introduction to FQHE, FAQHE & FCI

The Quantum Hall Effect requires a strong magnetic field environment to be realized. However, the emergence of the Haldane Model and Chern Insulators allowed the Quantum Hall Effect to be realized in lattice systems without an external magnetic field. This phenomenon is called the “Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect”. In Chern Insulators, the non-trivial Berry Curvature distribution endows the lattice system with non-trivial topological properties similar to the Quantum Hall Effect, or even further, Berry Curvature replaces the magnetic field (although Berry Curvature is defined in reciprocal space, while the magnetic field appears in real space). Discussions on Chern Insulators and other topological phases derived from this have also become hot topics in the field of condensed matter theory in recent years.

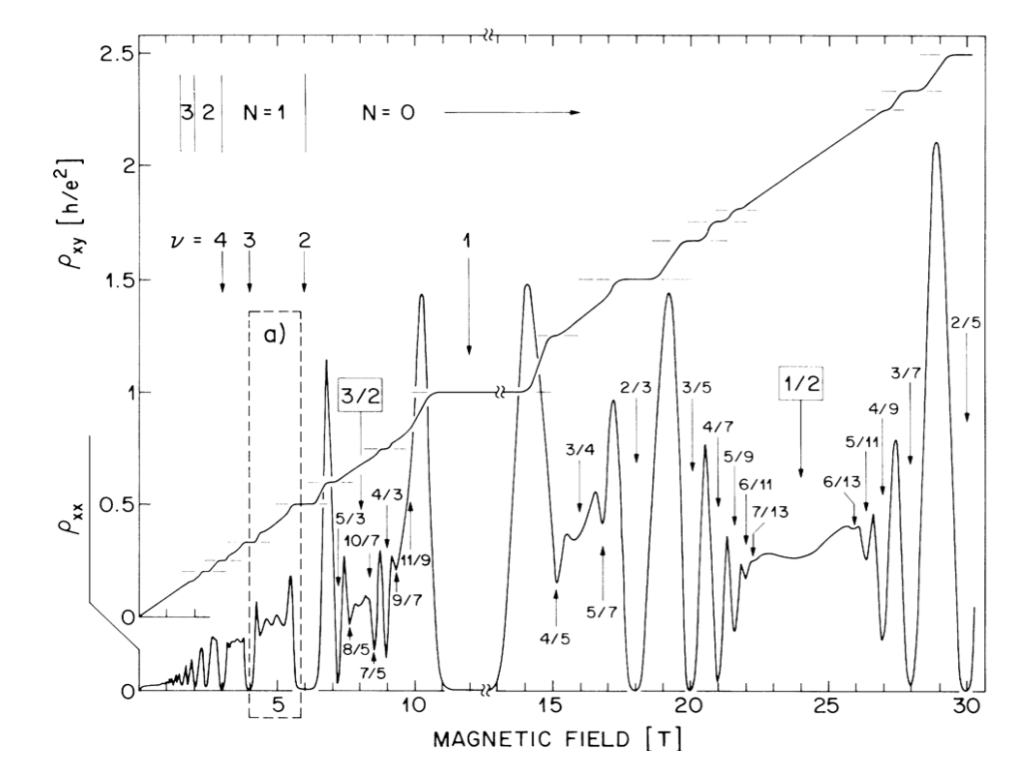

On the other hand, when the magnetic field strength is large enough that all electrons are degenerate in the Lowest Landau Level (LLL), especially when an electron occupies an integer (or fractional) number of quantum magnetic fluxes on average, the Fractional Quantum Hall Effect appears. Unlike the Quantum Hall Effect, Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect, or general topological insulators, the Fractional Quantum Hall Effect is the result of strong electron interactions degenerate in the LLL, whereas previous discussions were basically limited to non-interacting gapped Fermi systems.

Fractional Quantum Hall systems possess topological ground state degeneracy (GSD), fractional excitations, and anyonic statistics, which may be applied to fields such as topological quantum computing. However, the condition requiring a magnetic field stronger than that for the Quantum Hall Effect can “dissuade” many who wish to apply this effect.

Similar to various tenses in English grammar, we also want to combine “Anomalous” and “Fractional” to create a new Quantum Hall Effect, namely the “Fractional Anomalous Quantum Hall Effect” (FAQHE), abbreviated as “FAQ”.

specifically, we hope this phenomenon can be realized in lattice systems. Combining the realization of the Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect in Chern Insulators, physicists turned their attention to the topologically non-trivial Chern Band in Chern Insulators. Mimicking the fractionally filled LLL, they performed 1/3, 1/5, 1/7… electron fillings in the Chern Band and added electron-electron correlation terms (such as the Hubbard Model) to the system Hamiltonian to observe whether this fractionally filled Chern Insulator could exhibit phenomena similar to FQH systems (the previously mentioned GSD, fractional excitation, anyonic statistics, etc.).

In numerical simulations of systems such as fractional filling, topologically non-trivial Haldane Model, and Kagome Lattice, phenomena such as a finite many-body gap in the thermodynamic limit, non-trivial GSD, and fractional excitations were indeed observed. Physicists named this novel topological state of matter “Fractional Chern Insulator” (FCI).

Physics in L.L.L.

To “seamlessly connect” the Fractional Quantum Hall Effect in (near) free electron gas systems to the lattice systems of Chern Insulators, we first review the physics in the Lowest Landau Level (L.L.L.).

Hamiltonian of an electron in a magnetic field:

$$ \begin{aligned} H=\frac{1}{2 m}\left( \hat{\mathbf{p}} + e \mathbf{A}(\hat{\mathbf{r}}) \right)^2 = \frac{\boldsymbol{\pi}^2}{2m} \end{aligned} $$For a free electron gas in a constant external magnetic field, one can calculate Landau levels without selecting a specific gauge, or strictly solve for single-electron wave functions under Landau Gauge and Symmetric Gauge.

Analysis without Gauge

$$ \begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{\pi}=\mathbf{p}+e \mathbf{A}=m \dot{\mathbf{x}} \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} {\left[\pi_x, \pi_y\right]=-i e \hbar B} \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} a=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2 e \hbar B}}\left(\pi_x-i \pi_y\right) \text { and } a^{\dagger}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2 e \hbar B}}\left(\pi_x+i \pi_y\right) \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} {\left[a, a^{\dagger}\right]=1} \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} H=\frac{1}{2 m} \boldsymbol{\pi} \cdot \boldsymbol{\pi}=\hbar \omega_B\left(a^{\dagger} a+\frac{1}{2}\right) \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} E_n=\hbar \omega_B\left(n+\frac{1}{2}\right) \quad n \in \mathbf{N} \end{aligned} $$Readily, we obtain the structure of the Landau levels, but we do not know information such as the degeneracy of the Landau levels.

Landau Gauge

The Landau Gauge breaks translational symmetry in the x-direction, while $k_y$ is a good quantum number. The corresponding eigen-wavefunction is localized in the x-direction (harmonic oscillator wave function in x-direction + plane wave in y-direction).

$$ \begin{aligned} \nabla \times \mathbf{A}=B \hat{\mathbf{z}} \quad \mathbf{A}=x B \hat{\mathbf{y}} \end{aligned} $$Then the Hamiltonian is,

$$ \begin{aligned} H=\frac{1}{2 m}\left(p_x^2+\left(p_y+e B x\right)^2\right) \end{aligned} $$$p_y$ is a good quantum number, so the wave function can be written as:

$$ \begin{aligned} \psi_k(x, y)=e^{i k y} f_k(x) \end{aligned} $$The Hamiltonian for $p_y = \hbar k$ is easily seen to be a harmonic oscillator with a shifted origin:

$$ \begin{aligned} H_k=\frac{1}{2 m} p_x^2+\frac{m \omega_B^2}{2}\left(x+k l_B^2\right)^2 \end{aligned} $$Energy spectrum and wave function:

$$ \begin{aligned} E_n=\hbar \omega_B\left(n+\frac{1}{2}\right) \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \psi_{n, k}(x, y) \sim e^{i k y} H_n\left(x+k l_B^2\right) e^{-\left(x+k l_B^2\right)^2 / 2 l_B^2} \end{aligned} $$The degeneracy of the Landau Level can be considered as follows: if there are periodic boundary conditions in the y-direction, then $k\in \frac{2\pi}{L_y}\mathbb{N}$, and the harmonic oscillator wave function localized near $x = -kl_B^2$ must also satisfy $x \in [0,L_x]$. Thus, the degeneracy is:

$$ \begin{aligned} \mathcal{N}=\frac{L_y}{2 \pi} \int_{-L_x / l_B^2}^0 \quad d k=\frac{L_x L_y}{2 \pi l_B^2}=\frac{e B A}{2 \pi \hbar} \end{aligned} $$This is equivalent to the number of quantum magnetic fluxes in the system:

$$ \begin{aligned} \mathcal{N}=\frac{A B}{\Phi_0} \quad \text { with } \quad \Phi_0=\frac{2 \pi \hbar}{e} \end{aligned} $$Later we will see that this can be analogized to the Wannier Function $W(x,k_y)$ in a Chern Insulator with $\mathcal{C}=1$, thereby providing a way to connect the FQH state with the FCI state. This content is introduced in detail in articles by XL Qi in the 2010s.

Symmetric Gauge

Symmetric Gauge:

$$ \begin{aligned} \mathrm{A}=-\frac{1}{2} \mathrm{r} \times \mathbf{B}=-\frac{y B}{2} \hat{\mathbf{x}}+\frac{x B}{2} \hat{\mathbf{y}} \end{aligned} $$Similarly analyzing another “momentum operator” and using its commutation relations to construct new “creation” and “annihilation” operators, this will give the degeneracy of Landau levels.

$$ \begin{aligned} \tilde{\boldsymbol{\pi}}=\mathbf{p}-e \mathbf{A} \quad\left[\tilde{\pi}_x, \tilde{\pi}_y\right]=i e \hbar B \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} {\left[\pi_i, \tilde{\pi}_j\right]=0} \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} b=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2 e \hbar B}}\left(\tilde{\pi}_x+i \tilde{\pi}_y\right) \quad \text { and } \quad b^{\dagger}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2 e \hbar B}}\left(\tilde{\pi}_x-i \tilde{\pi}_y\right) \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} {\left[b, b^{\dagger}\right]=1 \quad|n, m\rangle=\frac{a^{\dagger n} b^{\dagger m}}{\sqrt{n ! m !}}|0,0\rangle} \end{aligned} $$The wave function in the x-y plane can be described using complex space:

$$ \begin{aligned} z=x-i y \quad \text { and } \quad \bar{z}=x+i y \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \partial=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial x}+i \frac{\partial}{\partial y}\right) \quad \text { and } \quad \bar{\partial}=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial x}-i \frac{\partial}{\partial y}\right) \end{aligned} $$Thus:

$$ \begin{aligned} a=-i \sqrt{2}\left(l_B \bar{\partial}+\frac{z}{4 l_B}\right) \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} a^{\dagger}=-i \sqrt{2}\left(l_B \partial-\frac{\bar{z}}{4 l_B}\right) \end{aligned} $$It can be proven that the LLL wave function annihilated by $a$ has the following form:

$$ \begin{aligned} \psi_{L L L} \sim f(z) e^{-|z|^2 / 4 l_B^2} \end{aligned} $$The wave function corresponding to the lowest degeneracy quantum number $m=0$ within the LLL, annihilated by $b$, is:

$$ \begin{aligned} \psi_{L L L, m=0} \sim e^{-|z|^2 / 4 l_B^2} \end{aligned} $$Correspondingly, LLL wave functions for other degeneracy quantum numbers $m$ are:

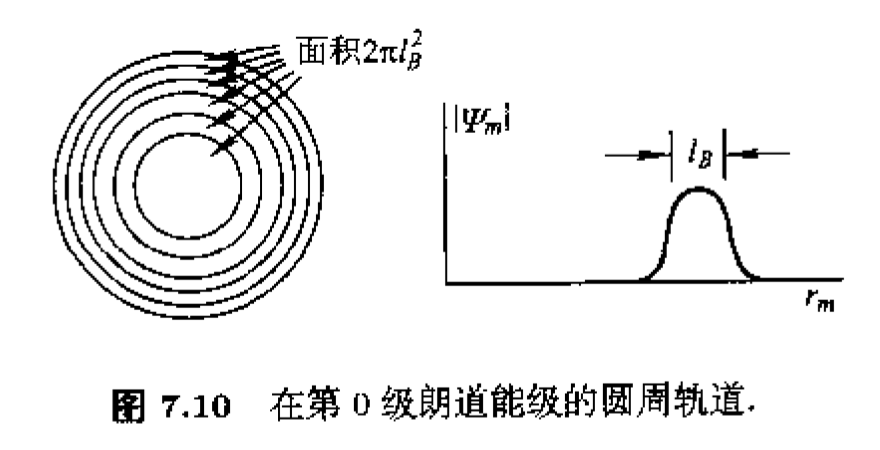

$$ \begin{aligned} \psi_{L L L, m} \sim\left(\frac{z}{l_B}\right)^m e^{-|z|^2 / 4 l_B^2} \end{aligned} $$It can be found that this function reaches a maximum approximately at $\rho = \sqrt{x^2+ y^2} = \sqrt{2ml_B^2}$, i.e., the wave function is localized on a ring with radius $\rho = \sqrt{2ml_B^2}$.

The degeneracy of the Landau level can also be calculated. For a finite disk system with radius R, $\rho_{max} = \sqrt{2m_{max}l_B^2} = \sqrt{2\mathcal{N}l_B^2}$, so

$$ \begin{aligned} \mathcal{N} = \frac{\pi R^2 B}{\Phi_0} \end{aligned} $$This gives the degeneracy of the Landau level from another perspective.

The eigen-wavefunction under Symmetric Gauge is localized near a certain radius. The angular momentum $J$ is a good quantum number, and its wave function can be written as a function of the independent variable $z = x + i y$ and its conjugate $\bar{z}$. The wave function in the L.L.L. can be written as the product of an analytic function $f(z)$ and an exponential factor $exp(-\bar{z}z/4l_B^2)$.

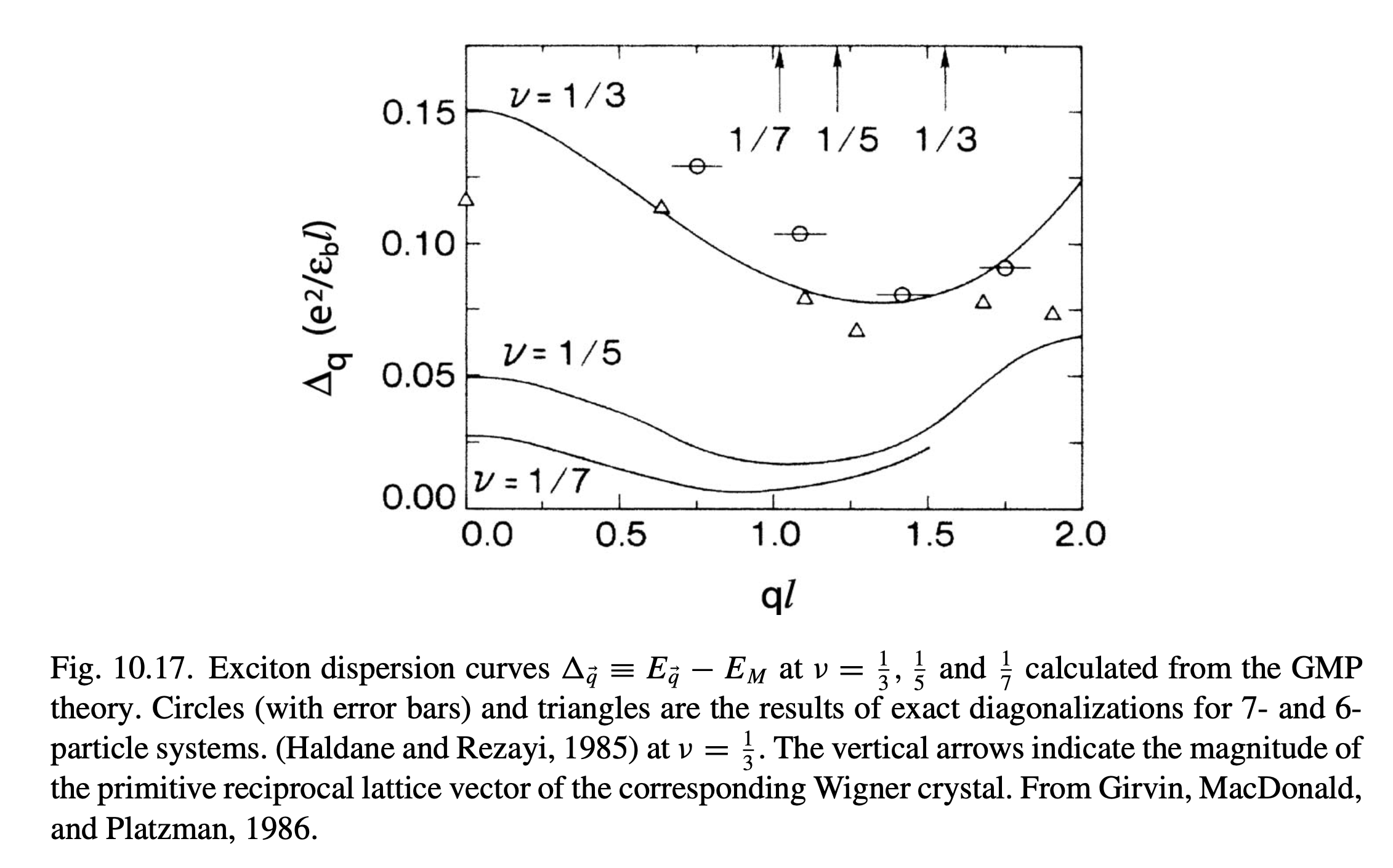

Later we will see that the analyticity of the function before the exponential factor in the L.L.L. wave function, i.e., the property that $f(z)$ is independent of $\bar{z}$, is very important for subsequently considering physics projected onto the L.L.L. (i.e., restricting the Hilbert space considered to wave functions on the L.L.L.). Considering physics projected onto the L.L.L. is very important for analyzing neutral excitations (magneto-roton excitation) in FQH. This is introduced in detail in the article by GMP (Girvin, MacDonald, Platzman) in the 80s regarding magneto-roton excitation in FQH systems. However, GMP’s analysis only provided an ansatz variational wave function for low-energy excitations in FQH systems; variational methods can only give an upper bound on excitation energy.

Later we will also see that the electron density operator projected onto the L.L.L. in FQH systems satisfies a special GMR Algebra (or called $W_\infty$ Algebra), which plays an important role in the emergence of the FCI phase and its stability analysis in Chern Insulators. To realize this Algebra in the Chern Band and thus realize a possible FCI phase, the Chern Band must possess nearly constant Berry Curvature and nearly constant Fubini-Study metric. This involves restrictions on the Quantum Geometry of the Chern Band. This is detailed in a series of articles by Rahul Roy et al. in the 2010s regarding FCI, GMR Algebra, and Geometric Stability.

Laughlin Wave Function

Laughlin ingeniously proposed (guessed) the form of the many-body wave-function for L.L.L. at 1/m filling.

First, consider the many-body wave function for filling factor $\nu = 1$. It should be the fully antisymmetrized form of single-body wave functions, i.e.:

$$ \begin{aligned} \Psi_m=\prod_{i < j}\left(z_{\imath}-z_{\jmath}\right)^m e^{\frac{1}{4 l_\beta^2} \sum\left|z_2\right|^2} \end{aligned} $$At this time, the power for particle i is $m(N-1)$. Thus, according to the relationship between angular momentum and radius for a single electron in LLL, we can obtain

$$ \begin{aligned} r_{\max }=\sqrt{2 \times m(N-1)} l_B \end{aligned} $$Thus, the degeneracy of the Landau level can be deduced as

$$ \begin{aligned} \mathcal{N} = \pi r_{max}^2/\Phi_0 \approx mN \end{aligned} $$Therefore, the Landau level filling factor is indeed $1/m$.

Normalization & Plasma Analogy

We often hear about Plasma analogy in FQH systems. This is actually a technique used when calculating the normalization coefficients of many-body wave functions for Laughlin States and other quasi-particle/quasi-hole excited states.

Through analogy, the modulus squared of the wave function is transformed into solving the classical partition function of a classical 2D electron gas at a certain finite temperature. The calculation of the normalization coefficient plays an important role in our analysis of the Berry Phase caused by the movement of quasi-hole excitations in FQH systems.

The modulus squared of the unnormalized Laughlin State is:

$$ \begin{aligned} \left|\Psi_m\left(z_1 \cdots z_N\right)\right|^2=e^{-\beta V\left(z_1 \cdot z_N\right)} \end{aligned} $$This is proportional to the probability distribution.

Define “pseudo-temperature” and energy as:

$$ \begin{aligned} \beta=\frac{2}{m} \quad V=-m^2 \sum_{i < j} \ln \left|z_i-z_{j}\right|+\frac{m}{4} \sum_i\left|z_i\right|^2 \frac{1}{l_B^2} \end{aligned} $$It can be seen that the energy $V$ corresponds to a 2D electron gas system with charge $m$ at positions $\{z_i\}_{i=1}^N$ on a uniform 2D background charge with density $-1/l_B^2$.

Review of 2D Plasma

Laplace equation for uniform 2D background charge and its potential $-\nabla^2\phi=\rho$ (omitting some physical constants):

$$ \begin{aligned} -\nabla^2\left(\frac{|z|^2}{4 l_B^2}\right)=-\frac{1}{l_B^2} \end{aligned} $$Potential distribution of a 2D point charge:

$$ \begin{aligned} -\nabla^2 \phi=2 \pi q \delta^2(\mathbf{r}) \Rightarrow \phi=-q \log \left(\frac{r}{l_B}\right) \end{aligned} $$Thus the interaction potential energy between point charges is:

$$ \begin{aligned} V = -m^2 \sum_{i < j} \ln \left|z_i-z_{j}\right| \end{aligned} $$The potential energy of point charges in the uniform background charge is:

$$ \begin{aligned} V = \frac{m}{4} \sum_i\left|z_i\right|^2 \frac{1}{l_B^2} \end{aligned} $$Returning to the calculation of the normalization coefficient:

$$ \begin{aligned} C = \int \prod_i d^2z_i \left|\Psi_m\left(z_1 \cdots z_N\right)\right|^2 = \int \prod_i d^2z_i e^{-\beta V\left(z_1 \cdot z_N\right)} \end{aligned} $$This is equivalent to integrating over all possible configurations of point charges according to probability $e^{-\beta V\left(z_1 \cdot z_N\right)}$, so the calculation of the normalization coefficient $C$ is transformed into the calculation of the partition function.

Anyonic Excitation

For an introduction to Anyons, please refer to the opening sections of Chapter 7 “Quantum Hall States” in Prof. Xiao-Gang Wen’s Many-Body Physics book. In conclusion, 2D systems can have anyonic statistics, while 3D systems only have Boson or Fermion statistics. This can be considered from the topological properties of the configuration space of n identical particles.

Next, we introduce quasi-particle and quasi-hole excitations in FQH.

Quasi-hole & Quasi-particle

The wave function of a quasi-hole is:

$$ \begin{aligned} \psi_{\text {hole }}(z ; \eta)=\prod_{i=1}^N\left(z_i-\eta\right) \prod_{k < l}\left(z_k-z_l\right)^m e^{-\sum_{i=1}^n\left|z_i\right|^2 / 4 l_B^2} \end{aligned} $$This implies that if any electron is located at $z = \eta$, the amplitude is 0, and the electron cloud density is 0 here, hence it is called “quasi-hole excitation”.

Furthermore, if there are m such holes all located at one position, the wave function is:

$$ \begin{aligned} \psi_{\mathrm{m}-\mathrm{hole}}(z ; \eta)=\prod_{i=1}^N\left(z_i-\eta\right)^m \prod_{k < l}\left(z_k-z_l\right)^m e^{-\sum_{i=1}^n\left|z_i\right|^2 / 4 l_B^2} \end{aligned} $$This is actually replacing the dynamical variable $z$ of an electron position with a parameter, equivalent to removing one electron. From this, one can naively infer that one hole is equivalent to removing $1/m$ electrons, and thus it is not difficult to guess its fractional charge and anyonic statistics.

Having “quasi-holes”, we wonder how to add “quasi-particles”. Naively, we want to divide by $\prod_{i=1}^N\left(z_i-\eta\right)$ in the system, but this is not a well-defined operation.

Realizing that dividing by a factor is somewhat equivalent to taking a partial derivative, plus some constant term corrections, we give the wave function for “quasi-particle” excitation:

$$ \begin{aligned} \psi_{\text {particle }}(z, \eta)=\left[\prod_{i=1}^N\left(2 \frac{\partial}{\partial z_i}-\bar{\eta}\right) \prod_{k < l}\left(z_k-z_l\right)^m\right] e^{-\sum_{i=1}^n\left|z_i\right|^2 / 4 l_B^2} \end{aligned} $$Again, Normalization & Plasma Analogy

Similarly, taking quasi-hole excitation as an example, we calculate the normalization coefficient of its many-body wave function. Putting all terms into the exponent and removing the temperature factor $\beta = 2/m$, we get the “pseudo-energy”:

$$ \begin{aligned} U\left(z_i;\xi\right)=-m^2 \sum_{i < j} \log \left(\frac{\left|z_i-z_j\right|}{l_B}\right)-m \sum_i \log \left(\frac{\left|z_i-\xi\right|}{l_B}\right)+\frac{m}{4 l_B^2} \sum_{i=1}^N\left|z_i\right|^2 \end{aligned} $$Where $-m \sum_i \log \left(\frac{\left|z_i-\eta\right|}{l_B}\right)$ represents the repulsive interaction potential between a “quasi-hole” with “charge” $1$ and charges with “charge” $m$. However, compared to the real system, we are still missing a term for the interaction between the “quasi-hole” and the “background charge”.

Therefore, we add this term and append a factor $e^{-\frac{1}{2 m l_B^2}|\xi|^2}$ before the exponential factor $e^{-\beta V\left(z_i,z_i^*;\xi, \xi^*\right)}$ to offset the effect of adding this term.

Now let’s calculate the normalization coefficient again:

$$ \begin{aligned} C = e^{-\frac{1}{2 m l_B^2}|\xi|^2} \int \prod_i d^2 z_i\left| \prod\left(\xi-z_i\right) \prod\left(z_i-z_j\right)^m e^{-\frac{1}{4 i_B^2}\left|z_i\right|^2}\right|^2 = e^{-\frac{1}{2 m l_B^2}|\xi|^2} \int \prod_i d^2 z_i e^{-\beta V\left(z_i,z_i^*;\xi, \xi^*\right)} \end{aligned} $$Where the $\int \prod_i d^2 z_i e^{-\beta V\left(z_i,z_i^*;\xi, \xi^*\right)}$ part is the classical partition function of this 2D Plasma system consisting of “charge $m$ at $\{z_i\}$” + “quasi-hole with charge 1 at $\xi$” + “uniform background charge”.

Qualitatively, since the partition function integrates over all charge configurations, the quasi-hole position $\xi$ as a parameter should in fact not affect the result of the partition function. Thus, the partition function part is a constant with respect to $\xi$, so we have

$$ \begin{aligned} C\left(\xi, \xi^*\right) = \text{const} \times e^{\frac{1}{2 l_B^2} \frac{1}{m}|\xi|^2} \end{aligned} $$The calculation of the normalization coefficient plays an important role in our analysis of the Berry Phase caused by the movement of quasi-hole excitations in FQH systems.

Berry Phase from a moving Quasi-hole

The phase change before and after the movement of a quasi-hole is:

$$ \begin{aligned} \left\langle\Psi^h\left[\xi(t+\Delta t), \xi^*(t+\Delta t)\right] \mid \Psi^h\left[\xi(t), \xi^*(t)\right]\right\rangle=e^{i \Delta t a \cdot x} \end{aligned} $$This is equivalent to:

$$ \begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{a} \cdot \dot{x}=i\left\langle\Psi^h\left[\xi(t), \xi^*(t)\right]\left|\frac{d}{d t}\right| \Psi^h\left[\xi(t), \xi^*(t)\right]\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} =\frac{d \xi}{d t} i\left\langle\Psi^h\left(\xi, \xi^*\right)\left|\frac{\partial}{\partial \xi}\right| \Psi^h\left(\xi, \xi^*\right)\right\rangle+\frac{d \xi^*}{d t} i\left\langle\Psi^h\left(\xi, \xi^*\right)\left|\frac{\partial}{\partial \xi^*}\right| \Psi^h\left(\xi, \xi^*\right)\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$Can be written as:

$$ \begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{a} \cdot d \boldsymbol{x}=a_{\xi} d \xi+a_{\xi^*} d \xi^* \end{aligned} $$Where $a_{\xi},\,a_{\xi^*}$ are the Berry Connections in the parameter space of the quasi-hole position $\xi$. Here defined in complex space, to ensure the phase is real, we have the above form.

The above quasi-hole excitation wave functions are already normalized.

The normalization coefficient of the unnormalized quasi-hole excitation wave function:

$$ \begin{aligned} \langle\Psi(\xi) \mid \Psi(\xi)\rangle=C\left(\xi, \xi^*\right) \end{aligned} $$Thus:

$$ \begin{aligned} i\left\langle\Psi^h\left(\xi, \xi^*\right)\left|\frac{\partial}{\partial \xi^{\prime}}\right| \Psi^h\left(\xi, \xi^*\right)\right)=i\left\langle\Psi(\xi)\left|\frac{1}{\sqrt{C\left(\xi, \xi^*\right)}} \frac{\partial}{\partial \xi} \frac{1}{\sqrt{C\left(\xi, \xi^*\right)}}\right| \Psi(\xi)\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} =i \int \prod_i d^2 z_i \Psi^*\left(\xi^*\right) \frac{1}{\sqrt{C}} \frac{\partial}{\partial \xi}\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{C}} \Psi(\xi)\right) \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} =i \frac{\partial}{\partial \xi} \int \prod_i d^2 z_2 \Psi^*\left(\xi^*\right) \frac{1}{C} \Psi(\xi)-i \int \prod_i d^2 z_2 \Psi^*\left(\xi^*\right)\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial \xi} \frac{1}{\sqrt{C}}\right) \frac{1}{\sqrt{C}} \Psi(\xi) \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} =-\mathfrak{\imath} \sqrt{C} \frac{\partial}{\partial \xi} \frac{1}{\sqrt{C}} \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} a_{\xi}=+\frac{i}{2} \frac{\partial}{\partial \xi} \ln C, \quad a_{\xi^*}=-\frac{i}{2} \frac{\partial}{\partial \xi^*} \ln C \end{aligned} $$Now the form of the normalization coefficient we derived earlier using a long string of Plasma Analogy comes into play. Since constant terms do not contribute to the derivative of $\ln C$, we have:

$$ \begin{aligned} a_{\xi}=i \frac{1}{m} \frac{1}{4 l_B^2} \xi^*, \quad a_{\xi^*}=-i \frac{1}{m} \frac{1}{4 l_B^2} \xi \end{aligned} $$This can be written as:

$$ \begin{aligned} a_{\xi}=-\frac{1}{m} q_e A^z, \quad a_{\xi^*}=-\frac{1}{m} q_e A^{z^*} \end{aligned} $$Where the magnetic vector potential on the complex plane is $A^z = \frac{1}{2}(A_x - iA_y)= \frac{1}{2} [( -\frac{By}{2} ) - i (\frac{Bx}{2})]$

Although the Berry Phase comes from the motion of the “quasi-hole” excitation position $\xi$ in parameter space, we can equivalently understand this effect as the AB phase produced by a particle with charge $e^\star$ moving in a magnetic field:

$$ \begin{aligned} \oint d \boldsymbol{x} \cdot \boldsymbol{a}=\left(-\frac{q_c}{m}\right) \oint d \boldsymbol{x} \cdot \boldsymbol{A} \end{aligned} $$Thus “quasi-hole” is equivalent to carrying a charge:

$$ \begin{aligned} e^{\star}=\frac{e}{m} \end{aligned} $$Similarly, if we analyze two quasi-hole excitations and their mutual statistics (specifically, the phase change caused by exchanging the positions of two holes; 0 for Bosons, $\pi$ for Fermions, and others for Anyons).

Anyonic Statistics

To calculate the normalization coefficient using Plasma Analogy, and thereby calculate the gauge potential, we need to add the interaction between “quasi-holes” and the interaction between “quasi-holes” and “background charge” to the exponential term of the previous “pseudo-partition function”.

As long as the positions of the two “quasi-hole” excitations are far enough apart, we can always assume that the partition function is independent of their positions. We can obtain the dependence of the normalization coefficient on the positions $\xi_1,\,\xi_2$ of the two “quasi-hole” excitations:

$$ \begin{aligned} C\left(\xi_1, \xi_2\right) \propto e^{\frac{1}{22_B^2} \frac{1}{m}\left(\left|\xi_1\right|^2+\left|\xi_2\right|^2\right)}\left|\xi_1-\xi_2\right|^{-\frac{2}{m}} \end{aligned} $$To consider their statistics, we let the second quasi-hole remain stationary and let the first quasi-hole go around it. This is equivalent to exchanging positions twice. At the same time, we must consider the AB phase corresponding to the equivalent charge $e^{\star}=\frac{e}{m}$ going around one loop of magnetic flux.

Actually, the overall phase change is the Berry Phase, but we insist on assigning a charge $e^{\star}=\frac{e}{m}$ to the quasi-hole to simulate the AB Phase, and assign mutual statistics corresponding to the total Berry Phase to them, giving us a more physical explanation for the generation of this Berry Phase.

Let:

$$ \begin{aligned} \xi=\xi_1 \text { and } \xi_2=0 \end{aligned} $$Gauge potential:

$$ \begin{aligned} a_{\xi}=i \frac{1}{m} \frac{1}{4 l_B^2} \xi^*-\frac{i}{2 m} \frac{\partial}{\partial \xi} \ln |\xi|^2=i \frac{1}{m} \frac{1}{4 l_B^2} \xi^*-\frac{i}{2 m} \frac{1}{\xi} \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} a_{\xi^*}=-i \frac{1}{m} \frac{1}{4 l_B^2} \xi+\frac{i}{2 m} \frac{1}{\xi^*} \text {. } \end{aligned} $$The line integral of the gauge potential along the trajectory of the first hole going around the second hole gives the total Berry Phase. We describe it using the AB Phase of the fractional charge and the mutual statistics of the two holes:

$$ \begin{aligned} \text{AB Phase} + 2\theta = \frac{e}{m} B \times \text { Area }+\frac{2 \pi}{m} \end{aligned} $$Thus the phase change for one exchange is:

$$ \begin{aligned} \theta=\frac{\pi}{m} \end{aligned} $$It is evident that fractional excitations indeed have mutual statistics in the form of anyons. Such anyonic statistics are of great significance for topological quantum computing.

Collective Neutral Excitation & GMP Algebra

Girvin, MacDonald, and Platzman analyzed the collective neutral excitation in FQH systems in the 80s. This collective excitation is an important factor in destabilizing the FQH phase. The GMP Algebra derived from it may also be significantly related to the stability of the FCI phase.

Therefore, we first analyze the collective neutral excitation in the FQH system, and then analyze how the GMP Algebra therein enters the analysis of the Many-Body Gap.

We will not analyze in detail how to calculate the Many-Body Gap, but only give a general idea. Detailed calculations can be found in the original papers by Girvin, MacDonald, and Platzman in the 80s, or in Chapter 10 of the book “Quantum Theory of the Electron Liquid” by Gabriele Giuliani and Giovanni Vignale.

Ansatz Excitation Wave Function

Girvin, MacDonald, and Platzman analogized the collective excitation of the $^4He$ system and proposed a trial wave function for the excited state:

$$ \begin{aligned} \left|\psi_{\vec{q}}\right\rangle=\hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}\left|\psi_0\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$Where $\left|\psi_0\right\rangle$ is the Laughlin wave function in the L.L.L. $\hat{n}_{\vec{q}}$ is the particle number operator in momentum space:

$$ \begin{aligned} \hat{n}_{\vec{q}}=\sum_{n, n^{\prime}, k_y, k_y^{\prime}}\left\langle n^{\prime}, k_y^{\prime}\left|e^{-i \vec{q} \cdot \vec{r}}\right| n, k_y\right\rangle \hat{a}_{n^{\prime}, k_y^{\prime}}^{\dagger} \hat{a}_{n, k_y} \end{aligned} $$And $\hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}$ is the operator projected onto the L.L.L.:

$$ \begin{aligned} \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}=\sum_{k_y, k_y^{\prime}}\left\langle 0, k_y^{\prime}\left|e^{-i \vec{q} \cdot \vec{r}}\right| 0, k_y\right\rangle \hat{a}_{0, k_y^{\prime}}^{\dagger} \hat{a}_{0, k_y} \end{aligned} $$Since applying the operator might map components in the L.L.L. to higher Landau Levels, which would increase the energy of our trial solution, we remove this part through projection.

Such a trial solution, which is low-energy and retains the correlations of the ground state wave function, should not differ much from the real excited state. Therefore, we can use the variational method to obtain an energy upper bound close to the excited state energy using the trial solution.

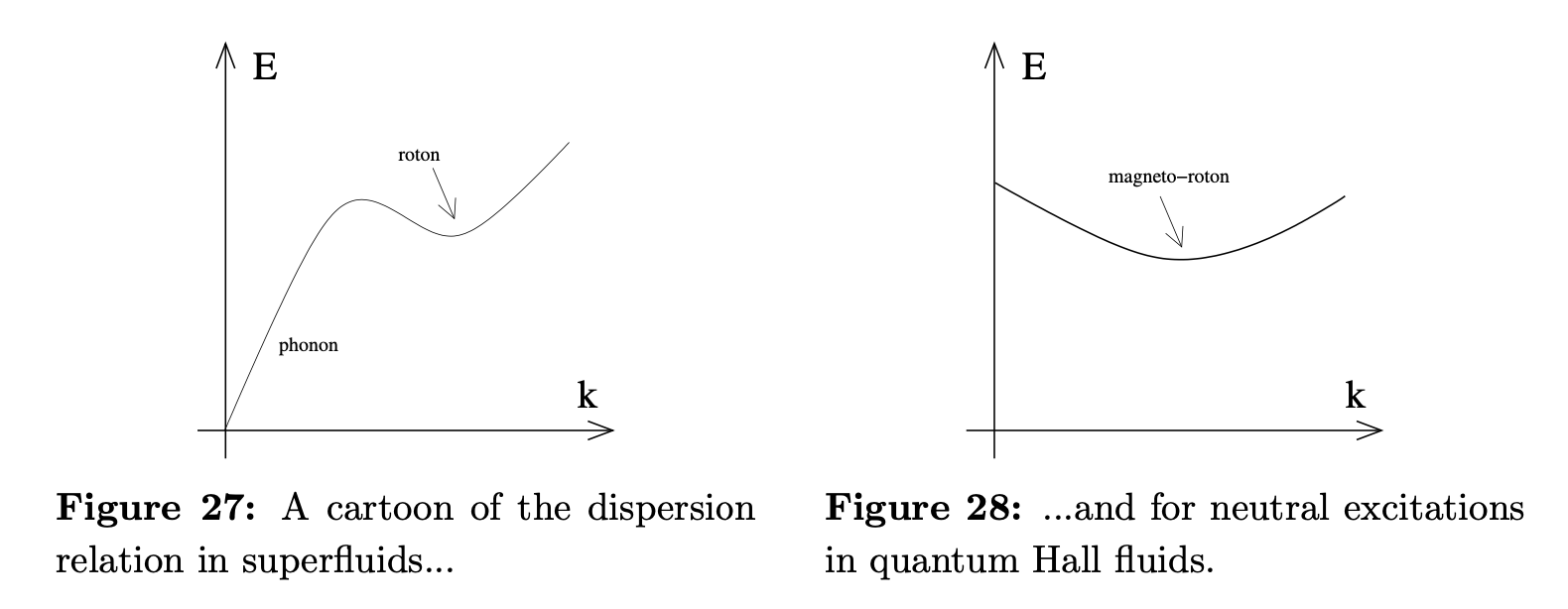

Incidentally, in the original GMP paper, this neutral collective excitation was named “Magneto-roton”, which is also related to the “roton” elementary excitation in boson systems. However, collective excitations in boson systems are gapless, while in our FQH system, there is a gap.

Projection to L.L.L.

The problem is, how to implement projection to L.L.L. The GMP paper tells us that for an operator in coordinate representation, we can make the following transformation:

$$ \begin{aligned} z_i^* \rightarrow 2 \ell^2 \frac{\partial}{\partial z_i} \end{aligned} $$Naively, operators in coordinate representation should be functions of $z,\,z^*$ (can always be Taylor Expanded), so we only need to know the result of projecting $z,\,z^*$ onto L.L.L. The wave function in L.L.L. has the following form:

$$ \begin{aligned} \psi(z)=f(z) e^{-\frac{|z|^2}{4 \ell^2}} \end{aligned} $$After acting with $z$, since $zf(z)$ is still an analytic function, the wave function remains in L.L.L. after being acted upon by $z$, so no transformation is needed.

$z^*$ is different, because $z^*f(z)$ will cause part of the wave function components to move to higher Landau Levels.

Recalling the raising/lowering operators for Landau Levels:

$$ \begin{aligned} a^{\dagger}=-i \sqrt{2}\left(l_B \partial-\frac{\bar{z}}{4 l_B}\right) \end{aligned} $$This is equivalent to:

$$ \begin{aligned} \bar{z}=4l_B^2 \partial-i \frac{4 l_Ba^{\dagger}}{\sqrt{2}} \end{aligned} $$It can be seen that $z^*$ can be written as a Landau Level raising operator (mapping to higher Landau Level) and a $\partial/\partial z$ part. Since $\partial f(z)/\partial z$ is still an analytic function, only the $\partial/\partial z$ part should remain after projection. Note that the previous definition was used here:

$$ \begin{aligned} z=x-i y \quad \text { and } \quad \bar{z}=x+i y \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \partial=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial x}+i \frac{\partial}{\partial y}\right) \quad \text { and } \quad \bar{\partial}=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial x}-i \frac{\partial}{\partial y}\right) \end{aligned} $$So there are some coefficient differences in the result compared to $z_i^* \rightarrow 2 \ell^2 \frac{\partial}{\partial z_i}$, but it is enough to understand why $z^*$ becomes $\partial_z$ after projection to L.L.L.

We have a more detailed derivation:

Let the wave function on L.L.L. be completely represented by the analytic function in front of the exponential:

$$ \begin{aligned} |\psi_f\rangle \equiv |f\rangle \end{aligned} $$Define its inner product (inner product weighted by an exponential factor):

$$ \begin{aligned} \langle g|f\rangle = \int g\left(z^*\right) f(z) e^{-\frac{|z|^2}{2 \ell^2}} d x d y \end{aligned} $$Thus the matrix element $\langle g|z^*|f\rangle$ of $z^*$ in the L.L.L. wave function space (Hilbert subspace) is:

$$ \begin{aligned} \int g\left(z^*\right) z^* f(z) e^{-\frac{|z|^2}{2 \ell^2}} d x d y \end{aligned} $$Write $z^*$ as obtained by operating $-2l^2 \partial_z$ on the exponential factor:

$$ \begin{aligned} \int g\left(z^*\right)\left[ - 2 \ell^2 \frac{\partial}{\partial z} e^{-\frac{|z|^2}{2 \ell^2}}\right] f(z) d x d y \end{aligned} $$Perform integration by parts, and using $\partial_z g(z^*) = 0$, we have

$$ \begin{aligned} \int g\left(z^*\right)\left[2 \ell^2 \frac{\partial}{\partial z} f(z)\right] e^{-\frac{|z|^2}{2 \ell^2}} d x d y = \langle g |2 \ell^2 \frac{\partial}{\partial z}f\rangle \end{aligned} $$Note that here $2 \ell^2 \frac{\partial}{\partial z}$ only acts on the analytic function $f(z)$ in front of the exponential.

There is another problem. If there are both $z$ and $z^*$, they can be exchanged arbitrarily in the integral, but $2 \ell^2 \frac{\partial}{\partial z}$ cannot be exchanged arbitrarily with $z$.

Let’s consider the projection result of $zz^*$:

$$ \begin{aligned} \int g\left(z^*\right) z z^* f(z) e^{-\frac{-4}{2}} d x d y=\int g\left(z^*\right)\left[2 \ell^2 \frac{\partial}{\partial z} z f(z)\right] e^{-\frac{-3 x}{2 z}} d x d y \end{aligned} $$It is visible that during integration by parts, $\partial_z$ will definitely include the analytic parts containing $z$ except for the exponential factor. This is equivalent to putting all $\partial_z$ to the far left, so as to “act from the left” on all $z$ operators.

So when doing projection, we first write the operator as a function of $z,\,z^*$, then move the $z^*$ parts to the left, i.e., normal ordering, and then make the substitution $z_i^* \rightarrow 2 \ell^2 \frac{\partial}{\partial z_i}$, which implements the projection of general operators to L.L.L.

Next we can perform the projection:

$$ \begin{aligned} \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}=\sum_{j=1}^N \overline{e^{-i \vec{q}^{\cdot} \cdot \hat{r}_j}} =\sum_{j=1}^N \overline{e^{-i \mathrm{q} z_j^* / 2} e^{-i \mathrm{q}^* z_j / 2}} =\sum_{j=1}^N e^{-i q \ell^2 \frac{\partial}{\partial z_j}} e^{-i q^* z_j / 2} \end{aligned} $$We can use commutators to get another equivalent expression

$$ \begin{aligned} \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}=e^{-q^2 \ell^2 / 2} \sum_{j=1}^N e^{-i q^* z_j / 2} e^{-i q \ell^2 \frac{\partial}{\partial z_j}} \end{aligned} $$Variational Method for Excitation Spectrum

Knowing how to project the operator to L.L.L., we can calculate the energy of our trial solution.

$$ \begin{aligned} E_{\vec{q}}=\frac{\left\langle\psi_{\vec{q}}|\hat{H}| \psi_{\vec{q}}\right\rangle}{\left\langle\psi_{\vec{q}} \mid \psi_{\vec{q}}\right\rangle} = \frac{\left\langle\psi_0\left|\hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}^{\dagger} \hat{H} \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}\right| \psi_0\right\rangle}{\left\langle\psi_0\left|\hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}^{\dagger} \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}\right| \psi_0\right\rangle} \end{aligned} $$Through commutation operations, transform the numerator into:

$$ \begin{aligned} E_0\left\langle\psi_0\left|\hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}^{\dagger} \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}\right| \psi_0\right\rangle+\frac{1}{2}\left\langle\psi_0\left|\left[\hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}^{\dagger},\left[\hat{H}, \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}\right]\right]\right| \psi_0\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$Thus it can be written as an expression of ground state energy + gap, where $\bar{f}/\bar{S}$ is the gap:

$$ \begin{aligned} E_{\vec{q}}=E_0+\frac{\bar{f}(\vec{q})}{\bar{S}(\vec{q})} \end{aligned} $$Where,

$$ \begin{aligned} \bar{f}(q) \equiv \frac{1}{2 N}\left\langle\psi_0\left|\left[\hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}^{\dagger},\left[\hat{H}, \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}\right]\right]\right| \psi_0\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \bar{S}(q) \equiv \frac{1}{N}\left\langle\psi_0\left|\hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}^{\dagger} \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}\right| \psi_0\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$Next, we calculate $\bar{f}$ and $\bar{S}$.

Entrance of GMP Algebra

First calculate $\bar{S}$. It can be proven that:

$$ \begin{aligned} \bar{S}(q)=S(q)-S_1(q) \end{aligned} $$Where $S$ is the ground state structure factor without projection:

$$ \begin{aligned} S(q) \equiv \frac{1}{N}\left\langle\psi_0\left|\hat{n}_{\vec{q}}^{\dagger} \hat{n}_{\vec{q}}\right| \psi_0\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$Since $\mathcal{P}_{LLL}|\psi_0\rangle=|\psi_0\rangle$,

$$ \begin{aligned} S(q) = \frac{1}{N}\left\langle\psi_0\left|\mathcal{P}_{LLL}\hat{n}_{\vec{q}}^{\dagger} \hat{n}_{\vec{q}}\mathcal{P}_{LLL}\right| \psi_0\right\rangle = \frac{1}{N}\left\langle\psi_0\left|\overline{\hat{n}_{\vec{q}}^{\dagger} \hat{n}_{\vec{q}}}\right| \psi_0\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$And $S_1$ is a constant:

$$ \begin{aligned} S_1(\vec{q})=1-e^{-q^2 \ell^2 / 2} \end{aligned} $$The derivation uses the commutation relation between $\partial$ and $z$, thereby relating $\overline{\hat{n}_{\vec{q}}^{\dagger} \hat{n}_{\vec{q}}}$ and $\hat{n}_{\vec{q}}^{\dagger} \hat{n}_{\vec{q}}$:

$$ \begin{aligned} \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}} \hat{\bar{n}}_{-\vec{q}} =\sum_j e^{-i q \ell^2 \frac{\partial}{\partial z_j}} e^{-i \frac{q^* z_j}{2}} \sum_k e^{+i q \ell^2 \frac{\partial}{\partial z_k}} e^{+i \frac{q^* z_k}{2}} =\sum_{j, k} e^{-i q \ell^2\left[\frac{\partial}{\partial z_j}-\frac{\partial}{\partial z_k}\right]} e^{-i q^*\left[\frac{z_j-z_k}{2}\right]} e^{-\frac{q^2 \ell^2}{2}\left[\frac{\partial}{\partial z_k}, z_j\right]} \end{aligned} $$Analyzing terms with $j=k$ and $j \neq k$, we get:

$$ \begin{aligned} \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}} \hat{\bar{n}}_{-\vec{q}} = \overline{\hat{n}_{\vec{q}} \hat{n}_{-\vec{q}}}+N\left[e^{-\frac{q^2 \ell^2}{2}}-1\right] . \end{aligned} $$Thus $\bar{S}(q)=S(q)-S_1(q)$ is proven, which transforms the calculation of projected operators into calculation before projection.

Since $\mathcal{P}_{LLL}|\psi_0\rangle=|\psi_0\rangle$, $\mathcal{P}_{LLL}^2 = \mathcal{P}_{LLL}$, it can be proven that the result remains unchanged if $\hat{H}$ in the formula is replaced by the projected operator.

$$ \begin{aligned} \bar{f}(q) \equiv \frac{1}{2 N}\left\langle\psi_0\left|\left[\hat{n}_{\vec{q}}^{\dagger},\left[\hat{\bar{H}}, \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}\right]\right]\right| \psi_0\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$Hamiltonian can only consider two-body interaction terms because single-body energies are all degenerate in L.L.L.:

$$ \begin{aligned} \bar{H}=\frac{1}{2 \mathcal{A}} \sum_{\vec{q}} v_q\left(\overline{\hat{n}_{\vec{q}}^{\dagger} \hat{n}_{\vec{q}}}-N\right) =\frac{1}{2 \mathcal{A}} \sum_{\vec{q}} v_q\left(\hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}^{\dagger} \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}-N e^{-q^2 \ell^2 / 2}\right) \end{aligned} $$In this way, we have transformed the calculation of the commutator in $\bar{f}$ into solving a more basic element, namely the commutator $\left[\hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{k}}, \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}\right]$.

The calculation of the commutator $\left[\hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{k}}, \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}\right]$ gives the closed Lie algebra form of the projected density operator, which is the famous GMP Algebra.

$$ \begin{aligned} \left[\hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{k}}, \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}\right]=\left(e^{\frac{\mathrm{k}^* q^2}{2}}-e^{\frac{\mathrm{kq}^* \ell^2}{2}}\right) \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{k}+\vec{q}} \end{aligned} $$Thus the calculation of $\bar{f}$ can be simplified:

$$ \begin{aligned} \bar{f}(q)=2 \frac{e^{-\frac{q^2 \ell^2}{2}}}{\mathcal{A}} \sum_{\vec{k}} \sin ^2\left(\frac{\left(\vec{q} \times \vec{k} \ell^2\right) \cdot \vec{e}_z}{2}\right) \bar{S}(k)\left[v_{|\vec{k}-\vec{q}|} e^{\vec{k} \cdot \vec{q} \ell^2} e^{-\frac{q^2 \ell^2}{2}}-v_k\right] \end{aligned} $$We will not repeat further calculations for $\bar{f},\,\bar{S}$ and many-body here. What is important is that we have seen how GMP Algebra enters the calculation of the many-body gap. Although the variational method here only gives an upper bound, numerical results show that this approximation is already very accurate.

Where at $q\rightarrow0$, the system has a finite gap, and the minimum value of the gap appears around $q \sim 1/l_B$, which is still a finite many-body gap. This gap of neutral collective excitation may have a significant impact on the stability of FQH and the FCI phase to be studied later.

GMP Algebra & Geometric Stability Hypothesis

We restate the essence of GMP Algebra:

$$ \begin{aligned} \left[\hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{k}}, \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{q}}\right]=\left(e^{\frac{\mathrm{k}^* q^2}{2}}-e^{\frac{\mathrm{kq}^* \ell^2}{2}}\right) \hat{\bar{n}}_{\vec{k}+\vec{q}} \end{aligned} $$Further derivation shows it is equivalent to:

$$ \begin{aligned} {\left[\bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_1}, \bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_2}\right]=2 i \exp \left(\frac{\mathbf{q}_1 \cdot \mathbf{q}_2 \ell_B^2}{2}\right) \sin \left(\frac{\mathbf{q}_1 \wedge \mathbf{q}_2 \ell_B^2}{2}\right) \bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_1+\mathbf{q}_2}} \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \mathbf{q}_1 \wedge \mathbf{q}_2 \equiv \hat{\mathbf{z}} \cdot\left(\mathbf{q}_1 \times \mathbf{q}_2\right) \end{aligned} $$If using another definition:

$$ \begin{aligned} \mathcal{P} \rho_{\mathbf{q}} \mathcal{P}=e^{-q^2 \ell_B^2 / 4} e^{i \mathbf{q} \cdot \mathbf{R}} \equiv e^{-q^2 \ell_B^2 / 4} \bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}} \end{aligned} $$Then the leading exponential factor can be eliminated, obtaining another equivalent GMP/$W_\infty$ Algebra:

$$ \begin{aligned} {\left[\bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_1}, \bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_2}\right]=2 i \sin \left(\frac{\mathbf{q}_1 \wedge \mathbf{q}_2 \ell_B^2}{2}\right) \bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_1+\mathbf{q}_2}} \end{aligned} $$In the analysis of FCI, a very important approach is to reproduce the GMP Algebra of the momentum space particle number operator $\hat{\bar{\rho}}_q$ projected onto L.L.L. in lattice systems, because this is most relevant to the neutral collective excitation that can most destabilize the FQH state.

To reproduce this GMP algebraic structure of FQH in lattice systems, we need special band geometry. The hypothesis linking band geometry, GMP Algebra, and FCI stability is the Geometric Stability Hypothesis. It plays a significant role in analyzing whether the FCI state appears and its stability in theory, numerics, and experiments.

Of course, completely replicating the algebraic structure of FQH should be a necessary condition for the emergence of FCI, not completely equivalent to the condition for the emergence of the FCI state. Theories in this aspect await further research.

Numerically, the Geometric Stability Hypothesis has been verified to some extent in various aspects such as ground state degeneracy and many-body gap.

Ground State Degeneracy

FQH systems have ground state degeneracy (GSD) related to the topological properties of the underlying manifold. This is an important factor for distinguishing FQH and FCI phases in numerics or experiments.

Here we use the creation and annihilation of quasi-particle/quasi-hole pairs as a simple example to illustrate the non-degeneracy of the system ground state and its relationship with the topological properties of the background manifold.

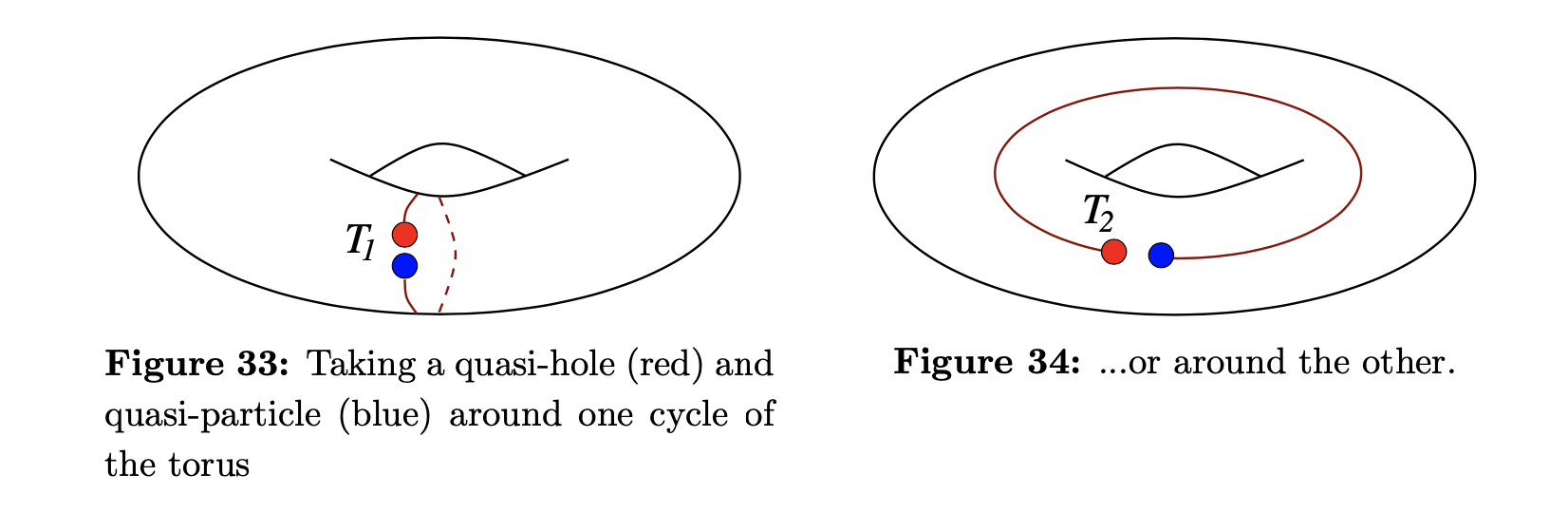

Consider an FQH system on a torus formed by identifying opposite edges of a square, i.e., an FQH system with periodic boundary conditions in both x and y directions. Now consider the creation and annihilation of quasi-particle/quasi-hole pairs. The quasi-particle/quasi-hole pair can go around the large circle of the torus (x-axis), created first and then annihilated; or around the small circle of the torus (y-axis), created first and then annihilated.

Denote the system evolution operators of these two processes as $\hat{T}_x$ and $\hat{T}_y$. Since the torus has periodic boundary conditions in both x and y directions, we can prove that the process $\hat{T}_x\hat{T}_y\hat{T}_x^{-1}\hat{T}_y^{-1}$ on the torus is topologically equivalent to a quasi-particle going around a quasi-hole once. Due to the fractional statistics of quasi-particles or quasi-holes, the phase produced by this process is $e^{2 \pi i/m}$, so we have:

$$ \begin{aligned} \hat{T}_x\hat{T}_y = e^{2 \pi i/m}\hat{T}_y\hat{T}_x \end{aligned} $$Since the whole process starts from the ground state, creates quasi-particle/quasi-hole excitation on the ground state, and then annihilates, returning to the ground state (possibly different from the original ground state), $\hat{T}_x$ and $\hat{T}_y$ only have matrix elements between ground states.

Whether degenerate or non-degenerate, $\hat{T}_x$ and $\hat{T}_y$ are matrices on the linear space based on the ground states $|0_1\rangle,\dots,|0_{GSD}\rangle$. Solving for the matrices corresponding to $\hat{T}_x$ and $\hat{T}_y$ is actually finding the group representation of $\hat{T}_x$ and $\hat{T}_y$ in the ground state space.

If the ground state $|0\rangle$ is non-degenerate, since both $\hat{T}_x$ and $\hat{T}_y$ processes eventually return to the ground state, they produce at most a phase,

$$ \begin{aligned} \hat{T}_x |0\rangle = e^{i \gamma_x} |0\rangle \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \hat{T}_y |0\rangle = e^{i \gamma_y} |0\rangle \end{aligned} $$But this immediately leads to a contradiction, because there would be

$$ \begin{aligned} \hat{T}_x \hat{T}_y |0\rangle = e^{i (\gamma_x + \gamma_y)} |0\rangle = \hat{T}_y \hat{T}_x |0\rangle \end{aligned} $$In fact, starting from the relation $\hat{T}_x\hat{T}_y = e^{2 \pi i/m}\hat{T}_y\hat{T}_x$ which tells us the non-Abelian nature of $\hat{T}_x,\,\hat{T}_y$, we should realize that their group representation in the ground state space will certainly not be 1-dimensional, i.e., the ground state must not be non-degenerate (it must be degenerate)!

Further analysis reveals that the group representation corresponding to the relation $\hat{T}_x\hat{T}_y = e^{2 \pi i/m}\hat{T}_y\hat{T}_x$ is at least m-dimensional.

In fact, for an FQH system with filling factor $\nu = 1/m$ defined on $T^2$ space, the ground state degeneracy is:

$$ \begin{aligned} GSD = m \end{aligned} $$The relationship with the topological properties of the FQH system’s background manifold is not hard to understand. Our derivation used:

“The process $\hat{T}_x\hat{T}_y\hat{T}_x^{-1}\hat{T}_y^{-1}$ on the torus is topologically equivalent to a quasi-particle going around a quasi-hole once”

For background manifolds with different genera, it is not difficult to imagine that more complex topological properties will lead to more exotic ground state degeneracy.

Effective Chern-Simons Theory

The low-energy effects of FQH systems can be described by the Chern-Simons action. This is actually an effective field theory after integrating out high-energy parts. It plays an important role in analyzing the fractional Hall conductance (linear response), fractional excitation, GSD, and fractional filling numbers corresponding to other multi-layer FQH. We will not elaborate here due to space limitations.

Flat Band

The Chern Band basically plays the role of the Landau Level in free electron gas, but to make interaction effects more significant, we adjust the bandwidth of the Chern Band so that the energy of electrons partially filled therein is basically degenerate. At the same time, we should have a large enough band gap so that wave functions between different Bands do not mix. This gives the first condition for the appearance of the FCI phase, the Flat Band condition:

When the dispersion relation of the Chern Band approaches a flat band, the kinetic energy of the electron states on the Chern Band becomes smaller, and the influence of electron-electron interaction becomes stronger, making it more likely for exotic many-body strongly correlated states like FCI to appear.

Twisted graphene, which has been hottest in recent years, is such a material. By adjusting parameters such as the relative twist angle $\theta$ between two layers of graphene, the relative ratio $\kappa$ of AA sublattice hopping and AB sublattice hopping strengths (which may be caused by phenomena like lattice relaxation), we can manipulate the dispersion relation near the Fermi surface to make it tend to be flat. Near the magic angle $\theta_c \approx 1.05^\circ$ and chiral limit $\kappa =0$, an almost strictly flat band can be obtained, and the band has topological properties (non-zero Chern number), becoming an important platform for studying the FCI phase.

Later we will also introduce the role of other lattice system properties besides dispersion relation on the appearance of the FCI phase, such as the distribution of Berry Curvature of the Chern Band in the Brillouin Zone (BZ), and the influence of Geometry factors such as Fubini-Study Metric of the Chern Band on the FCI phase.

Naively, requiring both special dispersion relation and special band geometry seems to make the condition for FCI appearance very harsh. But in fact, the dispersion relation and wave function of a lattice Hamiltonian (Berry Curvature, Fubini-Study Metric and other Band Geometry factors are actually related to the wave function) are somewhat independent. For a band with dispersion relation $\epsilon(k)$, we can always transform it into a 2-flat band dispersion relation while keeping the mapping from BZ to wave function space and its derived Berry Curvature and Band Geometry unchanged.

$$ \begin{aligned} \hat{H} = \sum_k \epsilon(k) |u_k\rangle \langle u_k| \rightarrow \hat{H}_{flat} = \sum_k \epsilon_0 |u_k\rangle \langle u_k| \end{aligned} $$The two are topologically equivalent as long as the gap between bands does not close during the transformation. In summary, in analytical analysis, we can study the dispersion relation $\epsilon(k)$ separately from the wave function $|u_k\rangle$ and its derived Berry Curvature $\mathcal{B}(k)$ and other band geometries.

Introduction to Quantum Geometry

Quantum states live in Hilbert Space. Since Hilbert Space has a well-defined inner product, we can use it to define “distance” and “metric” between quantum states, which gives a quantum geometric description of Hilbert Space, i.e., Quantum Geometry.

However, it should be noted that multiplying the state vector $|\psi\rangle$ by a non-zero complex number results in the same state, so real states should live in Projective Hilbert Space, which is isomorphic to $\mathbb{C} P^{n-1}$:

$$ \begin{aligned} \mathcal{P}_{\mathcal{H}} \simeq \mathbb{C} P^{n-1} \end{aligned} $$Naively defining “distance” between states:

$$ \begin{aligned} d s^2=\left\langle\partial_\mu \psi \mid \partial_\nu \psi\right\rangle d k^\mu d k^\nu \end{aligned} $$But this is not gauge invariant. The correct definition should be:

$$ \begin{aligned} d s^2=Q_{\mu \nu} d k^\mu d k^\nu \end{aligned} $$Where:

$$ \begin{aligned} Q_{\mu \nu} \equiv\left\langle\partial_\mu \psi \mid \partial_\nu \psi\right\rangle-\left\langle\partial_\mu \psi \mid \psi\right\rangle\left\langle\psi \mid \partial_\nu \psi\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$Its imaginary part is proportional to Berry Curvature:

$$ \begin{aligned} B_{\mu \nu} \equiv \operatorname{Im}\left[Q_{\mu \nu}\right] \end{aligned} $$Its real part is the Fubini-Study Metric:

$$ \begin{aligned} g_{\mu \nu} \equiv \operatorname{Re}\left[Q_{\mu \nu}\right] \end{aligned} $$Since Quantum metric should be similar to a general metric and have (semi-)positive definiteness, it can be proven:

$$ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{det}g_{\mu \nu} \geqslant\left|B_{\mu \nu}\right|^2 \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{Tr}g_{\mu \nu} \geqslant 2\left|B_{\mu \nu}\right| \end{aligned} $$FCI & Geometric Stability Hypothesis

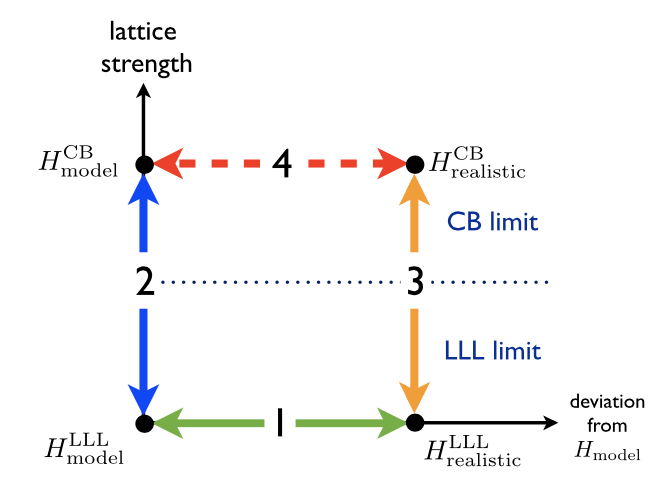

Now let’s return to the question mentioned at the beginning of this article: how to realize the FCI phase similar to the FQH effect in lattice systems. Besides the Flat Band condition, the previously mentioned Geometric Stability Hypothesis suggests that as long as we can reproduce the GMP Algebra of the projected density operator $\hat{\bar{\rho}}_q$ in the collective neutral excitation of the FQH system as much as possible, we are likely to realize the FCI phase in lattice systems.

Analogy of Interaction

First, we analogize the interaction in lattice and continuous systems:

$$ \begin{aligned} V=\frac{1}{2} \sum_{i, j} U_{i j} \hat{n}_i \hat{n}_j \end{aligned} $$Perform Fourier Transformation to get:

$$ \begin{aligned} V=\frac{1}{2} \sum_{\mathbf{q}} U(q) \hat{n}_{\mathbf{q}} \hat{n}_{-\mathbf{q}} \end{aligned} $$Eigen-wavefunction of the non-interacting part:

$$ \begin{aligned} |\mathbf{k}, \alpha\rangle=\gamma_{\mathbf{k}, \alpha}^{\dagger}|0\rangle \equiv \sum_a u_a^\alpha(\mathbf{k}) c_{\mathbf{k}, a}^{\dagger}|0\rangle \end{aligned} $$For the $\alpha$-band of interest, we analyze the physics projected onto the Chern Band, analogous to projecting onto L.L.L. in FQH.

The projection operator is:

$$ \begin{aligned} \mathcal{P}_\alpha=\sum_{\mathbf{k}} |\mathbf{k}, \alpha \rangle \langle\mathbf{k}, \alpha| \end{aligned} $$For a flat band, ignoring the single-body part, since projected $\overline{\rho_q \rho_{-q}}$ differs from $\bar{\rho_q}\bar{\rho_{-q}}$ only by a constant which can be omitted, the interaction Hamiltonian projected onto the Chern band is:

$$ \begin{aligned} H_{\mathrm{CB}, \alpha}^{\mathrm{eff}}=\frac{1}{2} \sum_{\mathbf{q}} U(\mathbf{q}) \bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q} ; \alpha} \bar{\rho}_{-\mathbf{q} ; \alpha} \end{aligned} $$Comparing with projection to L.L.L., both forms are basically consistent

$$ \begin{aligned} H_{\mathrm{LL}}^{\mathrm{eff}}=\frac{1}{2} \sum_{\mathbf{q}} V(\mathbf{q}) \mathrm{e}^{-q^2 \ell_B^2 / 2} \bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}} \bar{\rho}_{-\mathbf{q}} \end{aligned} $$Here $\mathrm{e}^{-q^2 \ell_B^2 / 2}$ is extracted because the definition here can eliminate the exponential term in GMP Algebra.

Lowest Order Correspondence

We take the long-wave approximation, thus we can expand the projected operator order by order in $q$. The result of expanding the projected density operator to $\mathcal{O}(q^2)$ is:

$$ \begin{aligned} \bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}}=P_\alpha-i P_\alpha \mathbf{q} \cdot \mathbf{r} P_\alpha-\frac{1}{2} P_\alpha(\mathbf{q} \cdot \mathbf{r})^2 P_\alpha + \mathcal{O}(q^3) \end{aligned} $$Calculating their commutator, we have:

$$ \begin{aligned} {\left[\bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_1}, \bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_2}\right] \approx \mathrm{i} \mathbf{q}_1 \wedge \mathbf{q}_2 \sum_{\mathbf{k}}\mathcal{B}_\alpha(\mathbf{k}) |\mathbf{k}, \alpha \rangle \langle\mathbf{k}, \alpha|} \end{aligned} $$Contrasting with the $\mathcal{O}(q^2)$ term of GMP Algebra, there should be:

$$ \begin{aligned} {\left[\bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_1}, \bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_2}\right]=i\left(\mathbf{q}_1 \wedge \mathbf{q}_2\right) \bar{B}_\alpha P_\alpha} \end{aligned} $$The projection operator $P_\alpha$ behind can actually be seen as the 0-th order approximation of $\bar{\rho}_{q_1+q_2}$,

$$ \begin{aligned} {\left[\bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_1}, \bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_2}\right] \approx \mathrm{i} \mathbf{q}_1 \wedge \mathbf{q}_2 \overline{\mathcal{B}}_\alpha \bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_1+\mathbf{q}_2}} \end{aligned} $$This actually shows that to reproduce GMP Algebra at $\mathcal{O}(q^2)$, it requires uniform distribution of Berry Curvature on BZ. This is the second condition that realizing FCI may need to satisfy, i.e., Flat Berry Curvature.

Deviation from the Flat Berry Curvature condition can be measured by the standard deviation of Berry Curvature on BZ. The larger the standard deviation, the further the density operator projected onto Chern Band is expected to be from GMP Algebra, thus the FCI phase is no longer stable.

We also see that at the lowest order, $\overline{\mathcal{B}}_\alpha$ replaces the role of $l_B^2$ in the GMP Algebra expression of FQH. This to some extent illustrates:

Berry Curvature indeed plays the role of replacing the real-space magnetic field.

For topologically trivial bands, the average value of Berry Curvature is obviously $\overline{\mathcal{B}}_\alpha=0$, so it will not reproduce GMP Algebra, and very likely there will be no FCI state. The FCI phase for systems with Chern number $\mathcal{C}>1$ is also currently a hot topic of research.

Higher Order Correspondence

Following the spirit of this long-wave expansion, we continue to expand the projected density operator to higher orders and observe the deviation of its commutator from GMP Algebra at each order.

For $\mathcal{O}(q^3)$, we have:

$$ \begin{aligned} {\left[\bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_1}, \bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_2}\right]} \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} =i \bar{B}_\alpha\left(\mathbf{q}_1 \wedge \mathbf{q}_2\right)\left[P_\alpha-i P_\alpha\left(\mathbf{q}_1+\mathbf{q}_2\right) \cdot \mathbf{r} P_\alpha\right] \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \quad-\frac{i}{2} \sum_{a, b, c}\left(\frac{q_{1 a} q_{2 b} q_{2 c}}{2}\left[P_\alpha r_a P_\alpha, P_\alpha\left(r_b Q_\alpha r_c+r_c Q_\alpha r_b\right) P_\alpha\right]\right. \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \left.\quad+\frac{q_{1 a} q_{1 b} q_{2 c}}{2}\left[P_\alpha\left(r_a Q_\alpha r_b+r_b Q_\alpha r_a\right) P_\alpha, P_\alpha r_c P_\alpha\right]\right), \end{aligned} $$Where,

$$ \begin{aligned} Q_\alpha=I-P_\alpha \end{aligned} $$It can be proved that when the Fubini-Study Metric:

$$ \begin{aligned} g_{a b}^\alpha(\mathbf{k})=\frac{1}{2} \sum_p\left[\left(\frac{\partial u_p^{\alpha *}}{\partial k_a} \frac{\partial u_p^\alpha}{\partial k_b}+\frac{\partial u_p^{\alpha *}}{\partial k_b} \frac{\partial u_p^\alpha}{\partial k_a}\right)\right. \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} \left.\quad-\sum_q\left(\frac{\partial u_p^{\alpha *}}{\partial k_b} u_p^\alpha u_q^{\alpha *} \frac{\partial u_q^\alpha}{\partial k_a}+\frac{\partial u_p^{\alpha *}}{\partial k_a} u_p^\alpha u_q^{\alpha *} \frac{\partial u_q^\alpha}{\partial k_b}\right)\right] \end{aligned} $$is invariant over the entire BZ, the projected density operator will satisfy the Generalized GMP Algebra,

$$ \begin{aligned} \left[\bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_1}, \bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_2}\right]=2 i \sin \left(\frac{\mathbf{q}_1 \wedge \mathbf{q}_2 \bar{B}_\alpha}{2}\right) e^{q_{1 l} g_{l m}^\alpha q_{2 m}} \bar{\rho}_{\mathbf{q}_1+\mathbf{q}_2} \end{aligned} $$In this way, we understand why Quantum Geometry enters the analysis of FCI stability. This is the spirit of the Geometric Stability Hypothesis.

Trace Condition

In the lowest order analysis, we used the standard deviation of Berry Curvature on BZ to characterize the degree of deviation of strongly correlated lattice systems from GMP Algebra. This is the second indicator characterizing FCI. The first is Band Flatness, which can be characterized by the standard deviation of the Chern Band dispersion relation.

In the literature, we will see a third FCI indicator, namely the Trace Condition. It actually characterizes the deviation of higher-order terms of the $\bar{\rho}_q$ commutator from GMP Algebra. Let’s briefly explain it below.

Previously we proved the inequality using the positive definiteness of Quantum Metric:

$$ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{tr}\left[g^\alpha(\mathbf{k})\right] \geqslant\left|B_\alpha(\mathbf{k})\right| \end{aligned} $$Note that the Berry Curvature before and after might differ by a factor of $2$.

Here we can give another proof:

$$ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{tr}\left[g^\alpha(\mathbf{k})\right]=\left\langle\mathbf{k}, \alpha\left|(x+i y)\left(I-P_\alpha\right)(x-i y)\right| \mathbf{k}, \alpha\right\rangle +i\left\langle\mathbf{k}, \alpha\left|\left[x\left(I-P_\alpha\right) y-y\left(I-P_\alpha\right) x\right]\right| \mathbf{k}, \alpha\right\rangle \end{aligned} $$Where

$$ \begin{aligned} A=\left(I-P_\alpha\right)(x+i y) P_\alpha \end{aligned} $$$$ \begin{aligned} C=\left(I-P_\alpha\right)(x-i y) P_\alpha \end{aligned} $$From the (semi-)positive definiteness of $AA^\dagger$ and $CC^\dagger$, we have:

$$ \begin{aligned} \left\langle\mathbf{k}, \alpha\left|A A^{\dagger}\right| \mathbf{k}, \alpha\right\rangle \geqslant 0, \quad\left\langle\mathbf{k}, \alpha\left|C C^{\dagger}\right| \mathbf{k}, \alpha\right\rangle \geqslant 0 \text {. } \end{aligned} $$Thus

$$ \begin{aligned} \operatorname{tr}\left[g^\alpha(\mathbf{k})\right] \geqslant\left|B_\alpha(\mathbf{k})\right| \end{aligned} $$Why care about this mathematical inequality? Because the equality sign “=” holds in this inequality if and only if the FS-metric is constant, and a constant FS-metric is the condition for higher-order terms to satisfy GMP Algebra.

So we can define a non-negative number $\operatorname{tr}\left[g^\alpha(\mathbf{k})\right] - \left|B_\alpha(\mathbf{k})\right|$ to characterize the deviation of higher-order terms from GMP Algebra. We define this quantity as “Trace Condition”, which is the third indicator of the FCI phase.

FCI Indicators

In summary, we obtained three indicators that (possibly) characterize the stability of FCI in fractionally filled Chern Bands:

- Band Flatness, characterized by the standard deviation of the Chern Band energy spectrum.

- Berry Curvature Flatness, characterized by the standard deviation of Berry Curvature. It describes the deviation of the Chern band from GMP Algebra at $\mathcal{O}(q^2)$ order.

- Trace Condition, characterized by the non-negative number $\operatorname{tr}\left[g^\alpha(\mathbf{k})\right] - \left|B_\alpha(\mathbf{k})\right| \geq 0$. It describes the deviation of the Chern band from GMP Algebra at $\mathcal{O}(q^3)$ and higher orders.

Finite Field FCI

In fact, we can also consider the effect of weak (but finite) magnetic fields on the stability of the FCI phase. We can still use the three FCI indicators mentioned above to characterize the stability of the FCI phase.

However, since the magnetic field breaks translational symmetry, enlarging the unit cell, the magnetic Brillouin zone is smaller than the original Brillouin zone, causing the Chern Band to fold and become multiple bands.

We can generalize Berry Curvature and FS metric to multi-band systems, and the projection also becomes projection onto these multiple bands split by the magnetic field. At this time, the Berry Connection will become non-Abelian, and the dimensions of Berry Curvature and FS metric will also expand.

However, these generalizations are natural, similar to generalizing from numbers to matrices, so the forms of the three indicators including Trace condition $\operatorname{tr}\left[g^\alpha(\mathbf{k})\right] - \left|B_\alpha(\mathbf{k})\right| \geq 0$ remain basically unchanged.

We will not elaborate here. Specific details can be found in a recent article by Ashvin simulating the FCI state in twisted graphene systems under zero field and finite magnetic field.

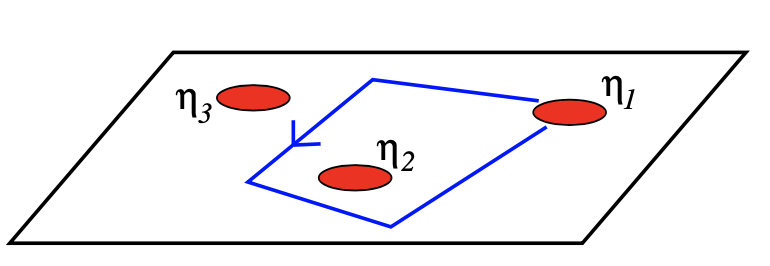

Wannier Function & L.L.L Wavefunction

XL Qi proposed a scheme to map the single-body Wannier Function in Chern Band to the single-body wave function of the QH system under Landau Gauge. Combined with the form of the many-body wave function given by Laughlin, we can reasonably guess the properties of the FCI state many-body wave function in the Chern Band.

Simply put, the single-particle wave function calculated by Landau gauge is an extended plane wave in the y-direction and a localized harmonic oscillator wave function in the x-direction;

In the Chern Band, due to the non-trivial band topology, this corresponds to topologically protected edge states. Therefore, general Fourier Transformation cannot obtain a Wannier Wavefunction localized in both x and y directions. However, one can perform Partial Fourier Transformation only in the x-direction to obtain a partial Wannier Function localized in the x-direction and extended in the y-direction.

Comparing these two single-particle wave functions, it is not difficult to relate them. Using the transformation from the single-particle wave function in electron gas to the Laughlin wavefunction, the partial Wannier Function in the above Chern Band can be written as a many-body wave function, thereby obtaining the wave function of the FCI state in the lattice system, as shown in the figure.

For specific details, please refer to the article by Qi, X. L., Generic wave-function description of fractional quantum anomalous Hall states and fractional topological insulators. Physical review letters, 107(12), 126803.